February is Career and Technical Education (CTE) month! As part of our 20th anniversary celebration, we want to highlight the great work our CTE Research Network (CTERN) continues to accomplish. The blog below highlights NCER’s conversation with the Equity Working Group of the IES-funded CTE Research Network.

The Equity Working Group (EWG) of the CTE Research Network (CTERN) has published a new resource for researchers on using an equity lens in developing and conducting CTE research: The Equity Framework for CTE Research. CTERN is hosting a free webinar on February 21st at 3:00 Eastern to provide an overview of the framework and how people can use it. In this blog, members of the Equity Working Group answered questions about the framework and why it is important.

The framework has a focus on equity, but equity can mean different things to different people. How does the EWG define equity in this framework?

We strongly believe that every student should have the opportunity to engage in quality educational experiences. Students who are interested should have access to CTE programs, regardless of their background characteristics. And school systems should invest in students so that they can succeed in these programs. Ultimately, we find ourselves quoting the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s definition because it neatly captures our position: “Every student has access to the educational resources and rigor they need at the right moment in their education across race, gender, ethnicity, language, disability, sexual orientation, family background, and/or family income.”

Why did the EWG members believe that there was a need for an equity framework for CTE research?

CTE has a long and complicated history, including extensive tracking under its previous incarnation as vocational education. The CTE Equity Working Group was very conscious of this history and wanted to take steps to help ensure that CTE research was helping to ameliorate current inequities. As we say in the framework, “We believe that infusing equity throughout our research is critical to ensuring that research can make a difference in promoting equitable learning experiences and outcomes for all students who participate in CTE.”

We also recognized that many researchers (including ourselves) want to use an equity lens to do their research but lack practical guidance in what that looks like. The working group believed that a framework with concrete examples and tips would help CTE researchers have a clearer picture of what to do and would provide a tool for helping them think differently about their work.

How did the EWG create the framework?

This was a collaborative process that grew out of our first CTE Research Network meeting in 2018 or 2019. A group of us realized that incorporating an equity lens into our work would help us better answer questions that matter to communities. We decided to form a working group, which ended up including around 20 or so researchers, practitioners, and policy staff. We read a lot of good frameworks from different organizations on improving our research practices, so we decided to invest our energy in seeing how it may be applied to a CTE context.

How is the framework structured and what are some key takeaways?

It is important to note what this framework is and is not. This framework is not intended as a methodological primer or a replication of existing research guidance; it is intended to encourage researchers to think about their own work through an equity lens.

The framework starts with a brief history of equity in CTE, a description of the process of creating the framework, a list of vocabulary (we believe having a common language is critical), and a statement of the values that underlie the framework.

The rest of the framework is then organized by six stages of research: 1) project management; 2) research design, 3) measurement and data collection, 4) data analysis, 5) cost and resource equity, and 6) reporting and dissemination. In each section, we include a description of how to implement the stage with an equity-focused lens, with questions for researchers to consider and potential barriers. Throughout, we have included examples from current and future CTE research. We are looking for more examples, so people should feel free to reach out to us at jedmunds@serve.org to share how they are doing this work.

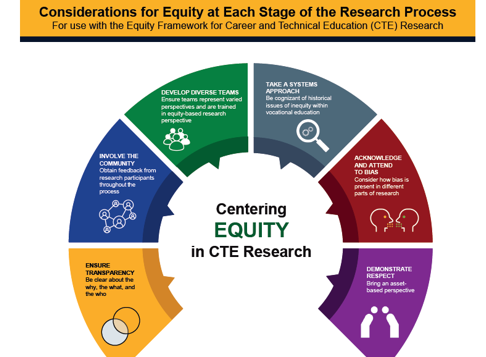

In creating summary products to go along with the framework, we identified six themes that cut across the different stages: ensure transparency, involve the community, develop diverse teams, take a systems approach, acknowledge and attend to bias, and demonstrate respect. These themes are summarized in an infographic.

How do you hope that people will use the framework?

We hope this will help start or further conversations among CTE researchers. We structured the framework around each stage of the research process, so anyone engaging in this work can find elements to incorporate or questions to consider individually and as a team, regardless of where they are in their work right now. For studies just getting off the ground, we did our best to illustrate how researchers can build an equity approach from the start of a project through its completion.

What are some examples of how the framework changed individual EWG members’ research practices?

Julie A. Edmunds (co-facilitator): Working on the framework has crystallized three high-impact equity-focused practices that I now try to infuse throughout my work. First, I pay much more attention to the role of systems in inequities. I try to look at upstream factors that might be causing disparities in educational outcomes as opposed to just documenting gaps that might exist between sub-groups. Second, when presenting those gaps (which we still do because it is useful information), I am much more conscious about how those gaps are displayed. For example, we focus on making sure that “White” is not considered the default category against which all others are compared. Third, we are creating processes to ensure that we share our findings with people who gave us the data. For example, we are sending practitioner-friendly products (such as briefs or infographics) to the school staff we interviewed whose insights formed the basis for some of our findings.

John Sludden (member): The framework has helped us think about our internal processes and keeps us focused on our audience, who we’re doing this for. I’m an analyst on the project, and I’ve been empowered to ask questions, conduct analyses, and present to our research partners at the New York City Department of Education. We’re currently thinking about ways to communicate findings to different audiences. At the moment, we’re working on a plan to share findings with principals of CTE high schools in New York City. Organizationally, we are also working on ways to directly engage students in the city, who know more about the system than we ever will. Similar to Julie, analytically, we have spent a lot of our time and attention on looking at the conditions under which students have not been well-served by the system, and ways that students may be better served by CTE.

This blog was produced by Corinne Alfeld (Corinne.Alfeld@ed.gov), program officer, NCER.