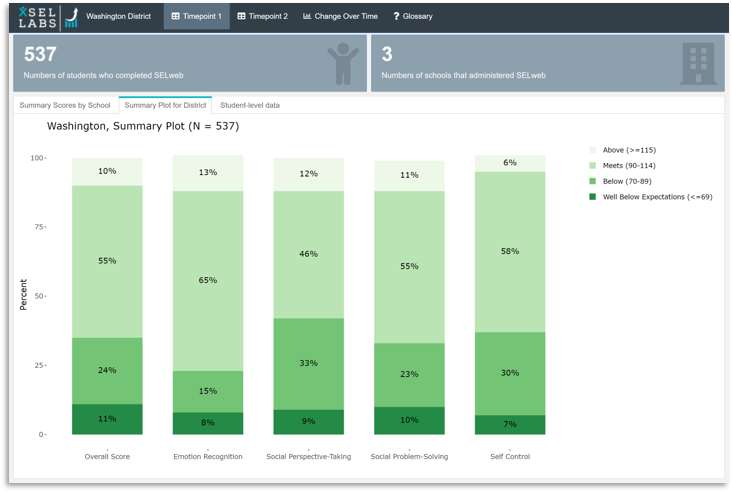

With a 2011 IES development grant, researchers at Rush University Medical Center, led by Clark McKown, created SELweb, a web-based system to assess the social-emotional skills in children in Kindergarten to Grade 3. The system (watch the video demo) includes illustrated and narrated modules that gauge children’s social acceptance with peers and assess their ability to understand others’ emotions and perspectives, solve social problems, and self-regulate. The system generates teacher reports with norm-referenced scores and classroom social network maps. Field trials with 8,881 children in seven states demonstrate that system produces reliable and valid measures of social-emotional skills. Findings from all publications on SELweb are posted here.

In 2016, with support from the university, McKown launched a company called xSEL Labs, to further develop and ready SELweb for use at scale and to facilitate the launch SELweb into the school marketplace. SELweb is currently used in 21 school districts in 16 states by over 90,000 students per year.

Interview with Clark McKown of Rush University Medical Center and xSEL Labs

From the start of the project, was it always a goal for SELweb to one day be ready to be used widely in schools?

CM: When we started our aspiration was to build a usable, feasible, scientifically sound assessment and it could be done. When the end of the grant got closer, we knew that unless we figured out another way to support the work, this would be yet another good idea that would wither on the vine after showing evidence of promise. In the last year and a half of the grant, I started thinking about how to get this into the hands of educators to support teaching and learning, and how to do it in a large-scale way.

By the conclusion of your IES grant to develop SELweb, how close were you to the version that is being used now in schools? How much more time and money was it going to take?

CM: Let me answer that in two ways. First is how close I thought we were to a scalable version. I thought we were pretty close. Then let me answer how close we really were. Not very close. We had built SELweb in a Flash based application that was perfectly suited to small-scale data collection and was economical to build. But for a number of reasons, there was no way that it would work at scale. So we needed capital, time, and a new platform. We found an outstanding technology partner, the 3C Institute, who have a terrific ed tech platform well-suited to our needs, robust, and scalable. And we received funding from the Wallace Foundation to migrate the assessment from the original platform to 3C’s. The other thing I have learned is that technology is not one and done. It requires continued investment, upkeep, and improvement.

What experiences led you to start a company? How were you able to do this as an academic researcher?

CM: I could tell you that I ran a children’s center, had a lot of program development experience, had raised funds, and all that would be true, and some of the skills I developed in those roles have transferred. But starting a company is really different than anything I’d done before. It’s exciting and terrifying. It requires constant effort, a willingness to change course, rapid decision-making, collaboration, and a different kind of creativity than the academy. Turns out I really like it. I probably wouldn’t have made the leap except that the research led me to something that I felt required the marketplace to develop further and to realize its potential. There was really only so far I could take SELweb in the academic context. And universities recognize the limitations of doing business through the university—that’s why they have offices of technology transfer—to spin off good ideas from the academy to the market. And it’s a feather in their cap when they help a faculty member commercialize an invention. So really, it was about finding out how to use the resources at my disposal to migrate to an ecosystem suited to continuing to improve SELweb and to get it into the hands of educators.

How did xSEL Labs pay for the full development of the version of SELweb ready for use at scale?

CM: Just as we were getting off the ground, we developed

a partnership with a research funder (the Wallace Foundation) who was interested in using SELweb as an outcome measure in a large-scale field trial of an SEL initiative. They really liked SELweb, but it was clear that in its original form, it simply wouldn’t work at the scale they required. So we worked out a contract that included financial support for improving the system in exchange for discounted fees in the out years of the project.

What agreement did you make with the university in order to start your company and commercial SELweb?

CM: I negotiated a license for the intellectual property from Rush University with the university getting a royalty and a small equity stake in the company.

Did anyone provide you guidance on the business side?

CM: Yes. I lucked into a group of in-laws who happen to be entrepreneurs, some in the education space. And my wife has a sharp business mind. They were helpful. I also sought and found advisors with relevant expertise to help me think through the initial licensing terms, and then pricing, marketing, sales, product development, and the like. One of the nice things about business is that you aren’t expected to know everything. You do need to know how and when to reach out to others for guidance, and how to frame the issues so that guidance is relevant and helpful.

How do you describe the experience of commercializing SELWeb?

CM: Commercialization is, in my experience, an exercise in experimentation and successive approximations. How will you find time and money to test the waters? Commercialization is an exciting and challenging leap from the lab to the marketplace. In my experience, you can’t do it alone, and even with great partners, competitive forces and chance factors make success scale hard to accomplish. Knowing what you don’t know, and finding partners who can help, is critical.

I forgot who described a startup as a temporary organization designed to test whether a business idea is replicable and sustainable. That really rings true. The experience has been about leaving the safe confines of the university and entering the dynamic and endlessly interesting bazaar beyond the ivory tower to see if what I have to offer can solve a problem of practice.

In one sentence (or two!), what would say is most needed for gaining traction in the marketplace?

CM: Figure out who the customer is, what the customer needs, and how what you have to offer addresses those needs. Until you get that down, all the evidence in the world won’t lead to scale.

Do you have advice for university researchers seeking to move their laboratory research into wide-spread practice?

CM: It’s not really practical for most university researchers to shift gears and become an entrepreneur. So I don’t advise doing what I did, although I’m so glad I did. For most university researchers, they should continue doing great science, and when they recognize a scalable idea, consider commercialization as an important option for bringing the idea to scale. My impression is that academic culture often finds commerce to be alien and somewhat grubby, which can get in the way. The truth is, there are whip-smart people in business who have tremendous expertise. The biggest hurdle for many university researchers will be to recognize that they lack expertise in bringing ideas to market, they will need to find that expertise, respect it, and let go of some control as the idea, program, or product is shaped by market forces. It’s also a hard truth for researchers, but most of the world doesn’t care very much about evidence of efficacy. They have much more pressing problems of practice to attend to. Don’t get me wrong—evidence of efficacy is crucial. But for an efficacious idea to go to scale, usability and feasibility are the biggest considerations.

For academics, getting the product into the marketplace requires a new set of considerations, such as: Universities and granting mechanisms reward solo stars; the marketplace rewards partnerships. That is a big shift in mindset, and not easily accomplished. Think partnerships, not empires; listening more than talking.

Any final words of wisdom in moving your intervention from research to practice?

CM: Proving the concept of an ed tech product gets you to the starting line, not the finish. Going to scale benefits from, probably actually requires, the power of the marketplace. Figuring out how the marketplace works and how to fit your product into it is a big leap for most professors and inventors. Knowing the product is not the same as knowing how to commercialize it.

____________________________________________________________________________

Clark McKown is a national expert on social and emotional learning (SEL) assessments. In his role as a university faculty member, Clark has been the lead scientist on several large grants supporting the development and validation of SELweb, Networker, and other assessment systems. Clark is passionate about creating usable, feasible, and scientifically sound tools that help educators and their students.

This interview was produced by Ed Metz of the Institute of Education Sciences. This post is the third in an ongoing series of blog posts examining moving from university research to practice at scale in education.