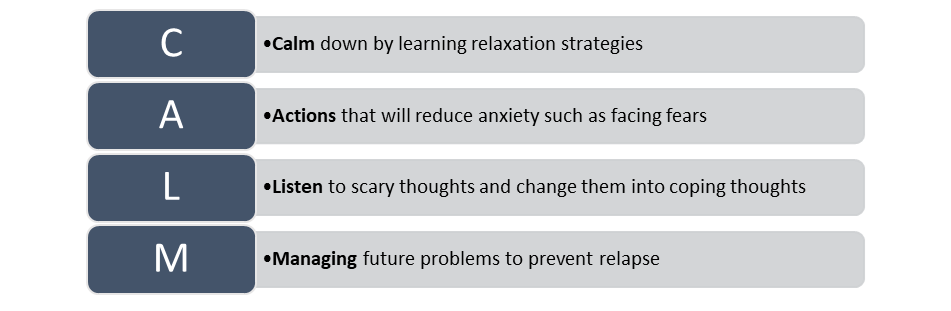

Many elementary school students experience anxiety that interferes with learning and achievement, but few receive services. To expand the network of support for these young students, IES-funded researchers have turned to school nurses as a potential front-line resource. The Child Anxiety Learning Modules (CALM) intervention incorporates cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and other evidence-based strategies for school nurses to use when a child has vague somatic complaints that often signal underlying anxiety.

In 2014, IES funded a Development and Innovation grant to support the development of CALM to enhance the capacity of elementary school nurses to help children with anxiety. Based on promising findings of feasibility and reduced anxiety and fewer school absences, the development team is launching an initial efficacy trial this fall to investigate the scale up potential of the CALM intervention.

We asked the developers of CALM—Golda Ginsburg (University of Connecticut School of Medicine) and Kelly Drake (Founder/Director of the Anxiety Treatment Center of Maryland; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine)—to answer a few questions for our blog. Here’s what they answered.

Can you describe how the CALM intervention was developed? What led you to develop an intervention for school nurses to implement?

We have been developing and evaluating psychosocial interventions for youth with anxiety for the last two decades, and we’ve learned a lot about effective, evidence-based strategies. We know that CBT, which consists of coping strategies that target the physical, cognitive, and behavioral manifestations of anxiety, is effective in helping youth manage and reduce anxiety. Unfortunately, we’ve also learned that most youth do not receive these—or any—services to help them. To address this gap in service utilization, our efforts have focused on ways of improving access to these therapeutic strategies by broadening the pool of potential providers. Given that early interventions can reduce the long-term consequences of untreated anxiety AND that youth with anxiety often complain of troublesome physical symptoms at school, we naturally thought of school nurses as a key provider with enormous potential. However, although nurses reported spending a lot of time addressing mental health issues, they received minimal training in doing so. That’s when the idea of the CALM intervention was born. We developed the initial CALM intervention using an iterative process in which versions of the intervention and its implementation procedures were sequentially refined in response to feedback from expert consultants, school nurses, children, parents, and school personnel until it was usable in the school environment by school nurses.

Was it part of the original plan to develop an intervention that could one day be used at scale in schools?

Yes—absolutely! Members of the National Association of School Nurses have been on our advisory team throughout to help us plan for how to scale up the intervention if we find it helps students.

What was critical to consider during the research to practice process?

A central focus was to minimize burden on school staff and to integrate the intervention within the goals and mission of schools’ interdisciplinary teams. Therefore, using a multidisciplinary support team was critical in taking the intervention from a research idea to an intervention that school nurses could delivered in their real-world practice setting—schools! As clinical psychologists, we also relied on our multidisciplinary team to ensure the intervention was usable by school nurses in terms of content and flexible and feasible for their busy school day. Indeed, school nurses and school nurse organizations provided critical support for the development of CALM with a focus on feasible strategies and methods for nurses to implement. They also provided invaluable feedback regarding perceived barriers to successful implementation of the intervention and adoption by nurses and school systems, and solutions to potential barriers and options for scaling up the intervention. We also relied on experts in school-based mental health programs and those with expertise in designing, evaluating, and implementing evidence-based prevention programs in schools. We also leveraged state-level expertise by consulting with school health experts in the Connecticut State Department of Education and the Connecticut Nurses Association regarding mental health education for nurses.

What model are you using for dissemination and sustainability?

A wide variety of methods will be used to disseminate findings from the current study to reach different stakeholders. We will present and publish findings at 1) national scientific and practitioner-oriented conferences, 2) Maryland and Connecticut State Departments of Education and participating school districts, and 3) in relevant peer-reviewed journals. In addition, should the findings reveal a beneficial impact of the intervention, we will have the final empirically supported training and intervention materials available for broad scale implementation. The CALM intervention will be packaged to include a training seminar, training videos, nurse intervention manual, child intervention handouts, consultation/coaching plan, and assessment materials. The research team will offer training seminars with all supporting materials to school nurse organizations at the national, state, and local levels. We will also engage nurse supervisors to identify nurses—or volunteer themselves—to become trainers for newly hired nurses in the future. Finally, our current Advisory Board, which consists of members of the National Association of School Nurses (NASN), school nurses, and researchers with expertise in large scale school-based mental health program implementation and evaluation, will assist in broad dissemination and sustainability efforts.

Golda S. Ginsburg, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Adjunct Professor at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, has over 25 years of experience developing and evaluating school-based interventions including school-based interventions for anxiety delivered by school clinicians, teachers, and nurses.

Kelly Drake, Ph.D., Founder/Director of the Anxiety Treatment Center of Maryland, Research Consultant with UConn, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry in the JHU School of Medicine has extensive training and experience in clinical research with anxious youth and training clinicians in delivering CBT for children.

This interview was produced by Emily Doolittle (Emily.doolittle@ed.gov) of the Institute of Education Sciences. This is part of an ongoing interview series with education researchers, developers, and partners who have successfully advanced IES-funded education research from the university laboratory to practice at scale.