It is clear that civic education is a priority in the United States. All U.S. states require students to take a civics or government course and many provide opportunities for students to perform community service or service learning to practice active citizenship.

However, reports illustrate that many young people are not being adequately prepared as citizens. For example, in the most recent National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) in Civics only one-quarter of students reached “proficient” in knowledge of key facts on the U.S. Constitution or the functions of government.

Amid calls to strengthen civic education, IES has funded several interventions that are leveraging technological innovation and game design to engage students. These projects are mainly funded through two IES programs—the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program and Education Research Grants in Education Technology.

Among the projects IES has funded:

- ECO (pictured above) is a game-based virtual environment where students collaboratively build a shared civilization and, in the process, apply democratic skills such as making rules and laws, analyzing data, and deliberation (watch video);

- Discussion Maker is a role-playing game where students debate a civic issue, such as freedom of speech. The technology assigns each student a role, facilitates analysis and using evidence to make an argument, and organizes face-to-face debates and deliberation (watch video);

- GlobalED2 is a role-playing game addressing a simulated global crisis (e.g., major oil spill or water scarcity) where students act as representatives of different countries governments. Students analyze the issue from the perspective of their country and negotiate with other countries to create a solution (watch video);

- EcoMUVE is a 3D multi-user virtual pond or forest environment where students apply inquiry-based practices to understand causal patterns in ecological science (watch video); and

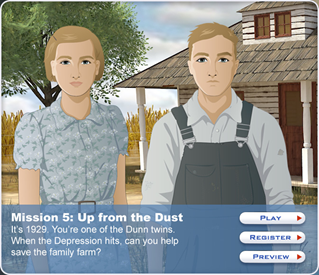

- Mission US’s Up from the Dust (pictured right) is a historical fiction adventure style game where students take on the role wheat farmers during the Great Depression in Texas 1929, and in doing so guide decisions by learning about the interaction of agriculture, the environment, and how government policies affect the economy (watch video).

Specific design elements of these games offer new ways to stimulate young people’s civic knowledge, skills, and engagement. For example:

All of these interventions employ game-based learning to motivate and engage students in new ways. For example, ECO is an unscripted “sandbox” where students create unique and personalized worlds, while Up from the Dust follows an adventure-based historical story. GlobalED2 and Discussion Maker employ role-playing and EcoMUVE guides inquiry-based virtual and real-world exploration.

Additionally, these programs all seek to build citizenship skills with cross-disciplinary content. For example, ECO, EcoMUVE, and GlobalED2 focus building citizen-science skills such as inquiry and analysis; Discussion Maker can apply content from almost any course within democratic debate; and Up from the Dust immerses students in a storyline with history, economics, and government concepts.

At the same time, these interventions also promote collaborative civic learning by simulating democratic processes for a whole class of students, both virtually and face-to-face. In ECO, students collaborate to create their own government with which they need to maintain through rules and laws. Discussion Maker and GlobalED2 use analysis, deliberation, and debates for individuals and groups of students. In EcoMUVE, students can conduct inquiry-based learning within the virtual environment. In Up from the Dust students engage in group discussions after gameplay to assess how specific decisions influenced results.

Several of these games also allow for feasible classroom implementation of what would otherwise be complex interventions. For example, some of the interventions provide real-time cues to students as they progress through the game, allowing a teacher to focus on facilitating overall instruction rather than coordinating every step of the game for every student.

To learn more about these projects, and to learn more about upcoming funding opportunities for the research and development and evaluation of technologies that support civic learning, visit the IES website or follow IES on Facebook and Twitter @IESResearch.

Ed Metz is a Research Scientist at IES, where he leads the SBIR and the Education Technology Research Grants programs.