By Cris de Brey

About 70 percent of first-time postsecondary students who started at 2-year or 4-year colleges in 2011-12 were either still enrolled or had attained a degree or certificate three years later. But a recent spotlight in the Condition of Education shows that there are differences in postsecondary persistence based on the type of institution attended and student demographics.

Given the economic and employment benefits of postsecondary education, it’s important that students who enroll in postsecondary education persist to degree completion. Persistent students are those that were enrolled at any institution or had attained a degree or certificate 3 years after first enrolling. The spotlight uses data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study and focuses on differences in persistence rates by demographic and college or university characteristics.

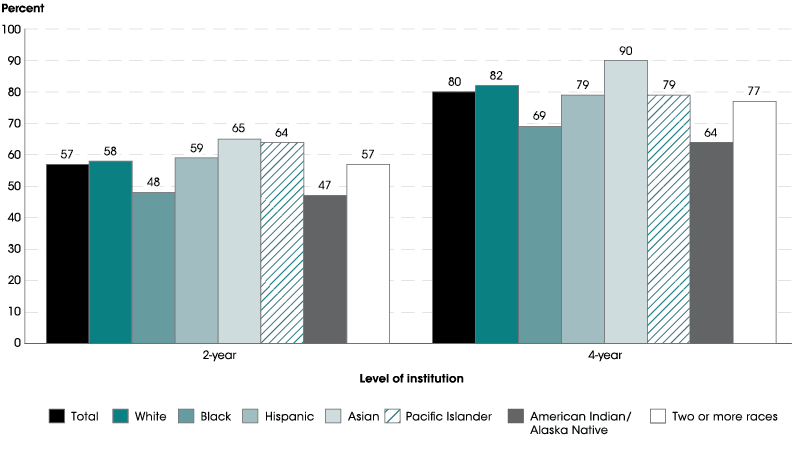

In spring 2014, the persistence rate for students who began at 2-year institutions in 2011–12 was 23 percentage points lower than for students who began at 4-year institutions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Persistence rates of first-time postsecondary students who began at 2- and 4-year institutions during the 2011–12 academic year, by race/ethnicity: Spring 2014

NOTE: Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Students who first enrolled during the 2011–12 academic year are considered to have persisted if they were enrolled at any institution in Spring 2014 or had attained a degree or certificate by that time.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2012/14 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:12/14). See Digest of Education Statistics 2016, table 326.50.

A gap between persistence rates at 2- and 4-year institutions was also observed for students who were White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and of Two or more races. The difference in persistence rates between students who began at 2- and 4-year institutions ranged from 19 percentage points for Hispanic students to 25 percentage points for White students and Asian students.

Among students who began at 4-year institutions, Asian students had a higher persistence rate as of spring 2014 than White students. Both Asian and White students had a higher persistence rate than Hispanic, Black, and American Indian/Alaska Native students.

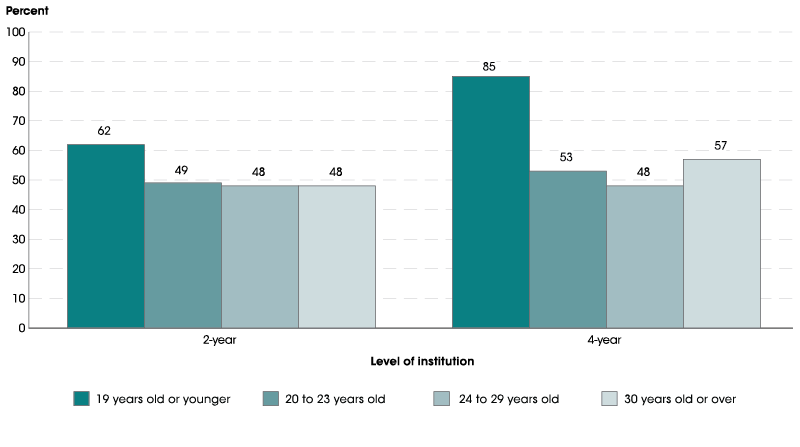

Looking at age differences, the persistence rate for students who were 19 years old or younger was higher than the rates for older students who began at both 2-year and 4-year institutions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Persistence rates of first-time postsecondary students who began at 2- and 4-year institutions during the 2011–12 academic year, by age when first enrolled: Spring 2014

NOTE: Students who first enrolled during the 2011–12 academic year are considered to have persisted if they were enrolled at any institution in Spring 2014 or had attained a degree or certificate by that time.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2012/14 Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS:12/14). See Digest of Education Statistics 2016, table 326.50.

There was no measurable difference between the persistence rates for the oldest three age groups who began at either type of institution.

The persistence rate for students 19 years old or younger who began at 2-year institutions was 24 percentage points lower than the rate for their same-aged peers who began at 4-year institutions. Unlike the youngest students, there were no measurable differences in persistence rates by level of institution for students who began their postsecondary education when they were 20 to 23 years old, 24 to 29 years old, and 30 years old or over.

For more information on postsecondary persistence rates, see the full spotlight on this topic in the Condition of Education.