Crime in the nation’s schools and college campuses has declined overall during the past two decades, according to a report released on April 17, 2019. Indicators of School Crime and Safety 2018 highlights new information on a wide array of data points, including youth opioid use, perceptions of bullying, and active shooter incidents in educational settings. The report also covers topics such as victimization, school conditions, school environment, safety and security measures at school, and criminal incidents at postsecondary institutions.

In 2017, students ages 12–18 experienced 827,000 total victimizations (i.e., theft and nonfatal violent victimization) at school and 503,800 total victimizations away from school. These figures represent a rate of 33 victimizations per 1,000 students at school, compared to 20 victimizations per 1,000 students away from school. From 1992 to 2017, the total victimization rate and rates of specific crimes—thefts, violent victimizations, and serious violent victimizations—declined for students ages 12–18, both at school and away from school.

This edition of Indicators of School Crime and Safety includes an analysis of active shooter incidents, which represent a small subset of the possible violent incidents that occur at schools. While rare, these events are of high concern to all those interested in the safety of our nation’s students. From 2000 to 2017, there were 37 active shooter incidents at elementary and secondary schools and 15 active shooter incidents at postsecondary institutions. During this period, there were 153 casualties (67 killed and 86 wounded) in active shooter incidents at elementary and secondary schools, and 143 casualties (70 killed and 73 wounded) in active shooter incidents at postsecondary institutions.

Between July 1, 2015 and June 30, 2016, the most recent period available, there were 18 homicides of school-age youth (ages 5–18) at a school out of the 1,478 homicides of school-age youth in the United States. During the same period, 3 of the 1,941 total suicides of school-age youth occurred at school.

In 2017, about 20 percent of students ages 12–18 reported being bullied at school during the school year. Between 2005 and 2017, the percentage of students who reported being bullied at school declined overall and for most of the student and school characteristics examined.

Of the students who were bullied in 2017, about 56 percent felt that those who had bullied them had the ability to influence what other students thought of them. A higher percentage of female students (62 percent) than male students (48 percent) reported that those who bullied them had the ability to influence what other students thought of them.

.png)

The new report included a special analysis that shows that the percentage of 8th-graders who reported using heroin during the past 12 months decreased from 1.4 percent in 1995 to 0.3 percent in 2017. The percentage also decreased from 1.1 to 0.2 percent for 10th-graders and from 1.1 to 0.4 percent for 12th-graders during the same period. This 0.4 percent of 12th graders reflects 15,900 students, who were recent users of heroin. The use of OxyContin and Vicodin during the past 12 months also generally decreased for 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders between 2005 (the first year of data collection for these survey items) and 2017.

.png)

There were also decreases for other types of substance abuse. The percentage of students in grades 9–12 who reported using alcohol at least once during the previous 30 days decreased from 47 to 30 percent between 2001 and 2017. Also, the percentage of students in grades 9–12 reporting marijuana use at least 1 time during the previous 30 days in 2017 (20 percent) was lower than the percentage for 2001 (24 percent).

Other findings – elementary and secondary schools

- About 99 percent of students ages 12–18 reported that they observed the use of at least one of the selected safety and security measures at their schools in 2017. The three most commonly observed safety and security measures were a written code of student conduct (95 percent), a requirement that visitors sign in and wear visitor badges or stickers (90 percent), and the presence of school staff (other than security guards or assigned police officers) or other adults supervising the hallway (88 percent).

- About 6 percent of students ages 12–18 reported being called hate-related words at school during the school year in 2017, representing a decrease from 12 percent in 2001. This percentage also decreased between 2001 and 2017 for male and female students as well as for White, Black, and Hispanic students.

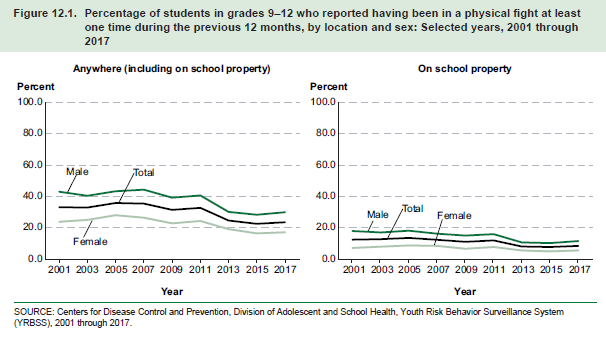

- The percentage of students in grades 9–12 who reported having been in a physical fight anywhere in the previous 12 months decreased between 2001 and 2017 (from 33 to 24 percent), as did the percentage of students in these grades who reported having been in a physical fight on school property (from 13 to 9 percent).

Other findings – postsecondary Institutions

- The number of on-campus crimes reported in 2016 was lower than the number reported in 2001 for every category except forcible sex offenses and negligent manslaughter offenses. The number of reported forcible sex crimes on campus increased from 2,200 in 2001 to 8,900 in 2016 (a 305 percent increase).

- Race, religion, and sexual orientation were the categories of motivating bias most frequently associated with the 1,070 hate crimes reported on college campuses in 2016.

To view the full report, please visit https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019047.