We are pleased to present The Condition of Education 2018, a congressionally mandated annual report summarizing the latest data on education in the United States. This report is designed to help policymakers and the public monitor educational progress. This year’s report includes 47 indicators on topics ranging from prekindergarten through postsecondary education, as well as labor force outcomes and international comparisons.

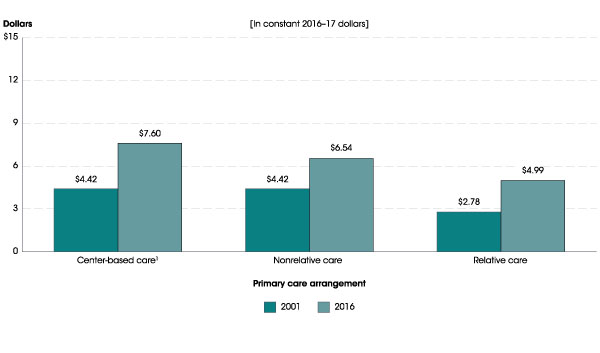

In addition to the regularly updated annual indicators, this year’s spotlight indicators highlight new findings from recent NCES surveys. The first spotlight indicator examines the choices and costs that families face as they select early childhood care arrangements. Drawing on data from the NCES National Household Education Survey, the indicator finds that early childhood care expenses were higher in 2016 than in 2001. For example, families’ average hourly out-of-pocket expenses for center-based care were 72 percent higher in 2016 ($7.60) than in 2001 ($4.42), in constant 2016–17 dollars. The indicator also finds that in 2016, some 57 percent of children under the age of 6 had parents who reported there were good choices for child care where they lived. Among children whose parents reported difficulty finding child care in 2016, some 32 percent cited cost as the primary reason. The complete indicator, Early Childhood Care Arrangements: Choices and Costs, contains more information about how these findings varied by family income, race/ethnicity, locale (urban, suburban, town, or rural), and children’s age.

Average hourly out-of-pocket child care expense for children under 6 years old and not yet in kindergarten whose families paid for child care, by primary type of child care arrangement: 2001 and 2016

1 Center-based arrangements include day care centers, Head Start programs, preschools, prekindergartens, and childhood programs.

NOTE: Estimates include only those children whose families paid at least part of the cost out of pocket for their child to receive nonparental care at least weekly.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Early Childhood Program Participation Survey of the National Household Education Surveys Program (ECPP-NHES: 2001 and 2016). See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, table 202.30c.

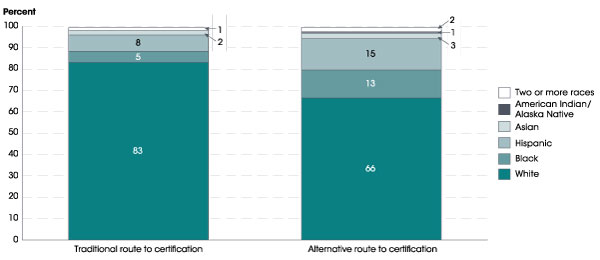

The second spotlight describes the characteristics of teachers who entered the teaching profession through an alternative route to certification program. Compared to those who entered through a traditional route, higher percentages of alternative route teachers in 2015–16 were Black (13 vs. 5 percent), Hispanic (15 vs. 8 percent), of Two or more races (2 vs. 1 percent), and male (32 vs. 22 percent), and lower percentages were White (66 vs. 83 percent). Overall, 18 percent of public school teachers in 2015–16 had entered teaching through an alternative route to certification program. The percentages were higher among those who taught career or technical education (37 percent), natural sciences (28 percent), foreign languages (26 percent), English as a second language (24 percent), math and computer science (22 percent), and special education (20 percent). The analysis also examines how the prevalence of alternative route teachers varies between charter schools and traditional public schools, between high and low poverty schools, and between schools that enroll high or low percentages of racial/ethnic minority students. For more findings from this analysis of data from the National Teacher and Principal Survey, see the complete indicator, Characteristics of Public School Teachers Who Completed Alternative Route to Certification Programs.

Percentage distribution of public elementary and secondary school teachers, by route to certification and race/ethnicity: 2015–16

NOTE: Teachers were asked whether they entered teaching through an alternative route to certification program, which is a program that was designed to expedite the transition of nonteachers to a teaching career (for example, a state, district, or university alternative route to certification program). Detail may not sum to totals because of rounding. Race categories exclude persons of Hispanic ethnicity. Data for American Indian/Alaska Native teachers who entered teaching through a traditional route and Pacific Islander teachers who entered teaching through traditional and alternative routes round to zero and are not displayed.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), “Public School Teacher Data File,” 2015–16. See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, table 209.24.

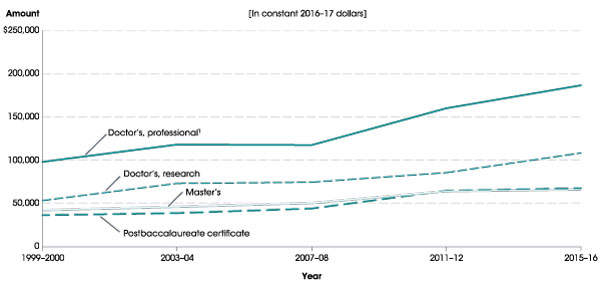

The third spotlight presents data on average student loan balances for students completing graduate degrees. Using data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, this indicator examines how average student loan balances changed between 1999–2000 and 2015–16, and how those trends varied by degree type. Among graduate school completers who had student loans for undergraduate or graduate studies, average student loan balances increased for all degree types (in constant 2016–17 dollars). For example, average student loan balances for students who completed research doctorate degrees, such as a Ph.D., doubled during this time period, from $53,500 to $108,400 (an increase of 103 percent). Average student loan balances increased by 90 percent for those who completed professional doctorate degrees, such as medical doctorates and law degrees (from $98,200 to $186,600). The complete indicator, Trends in Student Loan Debt for Graduate School Completers, also describes how average student loan balances varied among specific degree programs, such as medical doctorates, law degrees, and master’s degrees in business administration.

Average cumulative student loan balance for graduate school completers, by degree type: Selected years, 1999–2000 through 2015–16

1 Includes chiropractic, dentistry, law, medicine, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, and veterinary medicine.

NOTE: Data refer to students who completed graduate degrees in the academic years indicated. Includes student loans for undergraduate and graduate studies. Average excludes students with no student loans.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 1999–2000, 2003–04, 2007–08, 2011–12, and 2015–16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:2000, NPSAS:04, NPSAS:08, NPSAS:12, and NPSAS:16). See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, table 332.45.

The Condition includes an At a Glance section, which allows readers to quickly make comparisons within and across indicators, and a Highlights section, which captures key findings from each indicator. The report contains a Reader’s Guide, a Glossary, and a Guide to Sources that provide additional background information. Each indicator provides links to the source data tables used to produce the analyses.

As new data are released throughout the year, indicators will be updated and made available on The Condition of Education website. In addition, NCES produces a wide range of reports and datasets designed to help inform policymakers and the public. For more information on our latest activities and releases, please visit our website or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

By James L. Woodworth, NCES Commissioner