The transition into high school is characterized by growing academic demands, more diverse and complex social interactions, and increasing pressure associated with the looming transition into adult life and responsibilities. As part of an IES-funded measurement project, Drs. Michael Furlong, Erin Dowdy, and Karen Nylund-Gibson refined and validated the Social Emotional Health Survey-Secondary (SEHS-S-2020). The SEHS-S-2020 assesses the social-emotional assets of high school students and fits within multi-tiered systems of support and response-to-intervention frameworks schools regularly employ for the identification and care of students with learning or social-emotional needs. We asked the research team that developed the SEHS-S-2020 to tell us more about the development of the measure and how it is being used in schools.

What inspired you to develop the Social Emotional Health Survey-Secondary?

What inspired you to develop the Social Emotional Health Survey-Secondary?

We were motivated by two events between 2008 and 2013. First, while we were serving as local evaluators of two Safe Schools/Healthy Students (SSHS) projects in Santa Barbara County, our project school administrators and mental health professionals challenged us to consider alternative ways to assess social-emotional health and the impacts of these projects. Second, around the same time, Michael Furlong was editing the first edition of the Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools. Examining various positive psychological mindsets for the SSHS projects, we recognized that many of these constructs—such as hope, self-efficacy, and grit—had overlapping content. Based on this, we wanted to see if we could develop an efficient measure of positive psychology mindsets in adolescents.

The traditional mental health disorder literature uses comorbidity to describe the poor psychosocial outcomes for individuals experiencing more than one psychological disorder. We wondered whether students who report multiple social and psychological assets have enhanced developmental outcomes. The term we use for this "whole is greater than the sum of its parts" construct is covitality. Building on this concept, a significant effort of our work at the University of California, Santa Barbara has been to develop measures for schools to monitor social-emotional wellness. We created measures for primary and secondary schools and higher education institutions because fostering social-emotional health is ongoing and responsive to emerging developmental tasks.

How does the Social Emotional Health Survey-Secondary measure covitality?

Through an IES Measurement grant, we refined and validated the SEHS-Secondary form, which measures psychosocial strengths derived from the social emotional learning (SEL) and positive youth development (PYD) literature. SEHS-S-2020 assesses four related general positive social and emotional health domains that contribute to covitality.

- Belief in Self consists of three subscales grounded in constructs from self-determination theory literature: self-efficacy, self-awareness, and persistence.

- Belief in Others comprises three subscales derived from constructs found in childhood resilience literature: school support, peer support, and family support.

- Emotional Competence consists of three subscales: emotion regulation, empathy, and behavioral self-control.

- Engaged Living comprises three subscales grounded in constructs derived from the positive youth psychology literature: gratitude, zest, and optimism.

What did you find during the validation study?

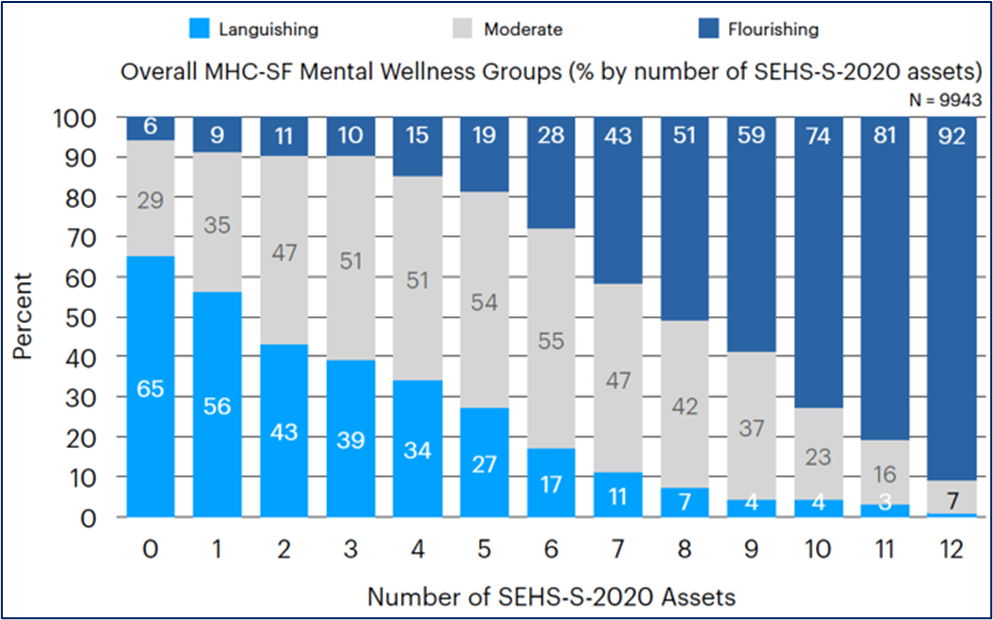

The validation project involved a cross-sectional sample of more than 100,000 California secondary school students in partnership with the California State Department of Education and WestEd. We also collected three years of longitudinal data with two collaborating school districts. Our goal was to develop a valid measure to support educator efforts to foster positive development. We wanted to document how the number of developmental assets was associated with mental well-being. This chart shows that students reporting many SEHS-S-2020 assets were substantially more likely to report flourishing well-being. Adolescents with more SEHS-S-2020 assets were less likely to report chronic sadness or past-year suicidal ideation (see the covitality advantage).

Did you have any unanticipated project outcomes?

Data collection immediately predated the COVID-19 pandemic. It provided a baseline to assess the effects of the pandemic and broader social divisiveness in the United States on student well-being. An important unanticipated outcome is that pre-pandemic social well-being declined substantially during and after remote learning.

Our project began collecting longitudinal data from middle and high school students in October 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. One participating school district asked us to administer the survey in October 2020 during remote learning and in October 2021 after the students returned to school, in order to understand remote learning's impacts on students' well-being. They also provided support for specific students who were not coping well. Our preliminary findings (paper in progress) showed that the students reported some diminished emotional well-being and global life satisfaction, but their social well-being decreased substantially from 2019 to 2021, about one-half of a standard deviation. Two macro-social items in particular declined markedly. One asks the students to express how often (in the past month) "they felt that society was a good place or becoming a better place for all people." A second asks them, "if the way that society works makes sense." Students reporting the steepest social well-being declines also reported substantial increases in chronic sadness and diminished global life satisfaction. These declines suggest that the broader impacts of the pandemic took a toll on the students.

How are schools using the resources your project developed?

There is a greater emphasis on evaluating social and emotional health and well-being than before. The SEHS-S-2020 is now a core component of the California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS), a biennial survey used by most California schools. It provides information about student wellness and risk-related behaviors. In addition, several California school districts have adopted the SEHS-S-2020 and other project-developed measures for their Tier 1 universal wellness screening, following up and providing counseling services and supports.

We are eager to see more schools using the resources from our project. For example, researchers in more than 20 countries have adapted the SEHS-S-2020 to explore cross-cultural aspects of well-being. An app to administer, score, report, and track social and emotional wellness with the SEHS-S-2020 now supports Tier 1 wellness monitoring.

Michael Furlong, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of School Psychology and holds a 2021-2022 Edward A. Dickson Emeritus Professorship at the University of California Santa Barbara.

Erin Dowdy, PhD., is a Professor in the Department of Counseling, Clinical, and School Psychology at the University of California Santa Barbara. She is a licensed psychologist and a nationally certified school psychologist.

Karen Nylund-Gibson, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Quantitative Methods in the Department of Education at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

This blog was produced by NCER Program Officer, Corinne Alfeld. Please contact Corinne.Alfeld@ed.gov for more information.