As part of our series recognizing the IES investment in Career and Technical Education (CTE) research, we interviewed Esther Prins, Professor at Pennsylvania State University, about her NCER-funded project, Career Pathways Programming for Lower-Skilled Adults and Immigrants: A Comparative Analysis of Adult Education Providers in High-Need Cities. This Researcher-Practitioner Partnership involves researchers at Pennsylvania State University working in collaboration with adult education providers in Chicago, Houston, and Miami to better understand how adult education programs are incorporating career pathways into their delivery models.

What is the education issue you and your partners trying to address?

Millions of U.S. adults have been left behind by the economy and rising education requirements for even minimum-wage jobs. Career pathway (CP) programs help adults prepare for employment and postsecondary education. Although recent federal policy (e.g., WIOA) has encouraged CP programming among adult education providers, there is little research to help guide practice and few opportunities for providers to learn about how their peers organize CP programs, who they serve, what outcomes they measure, and other program features.

What are career pathway programs in adult education?

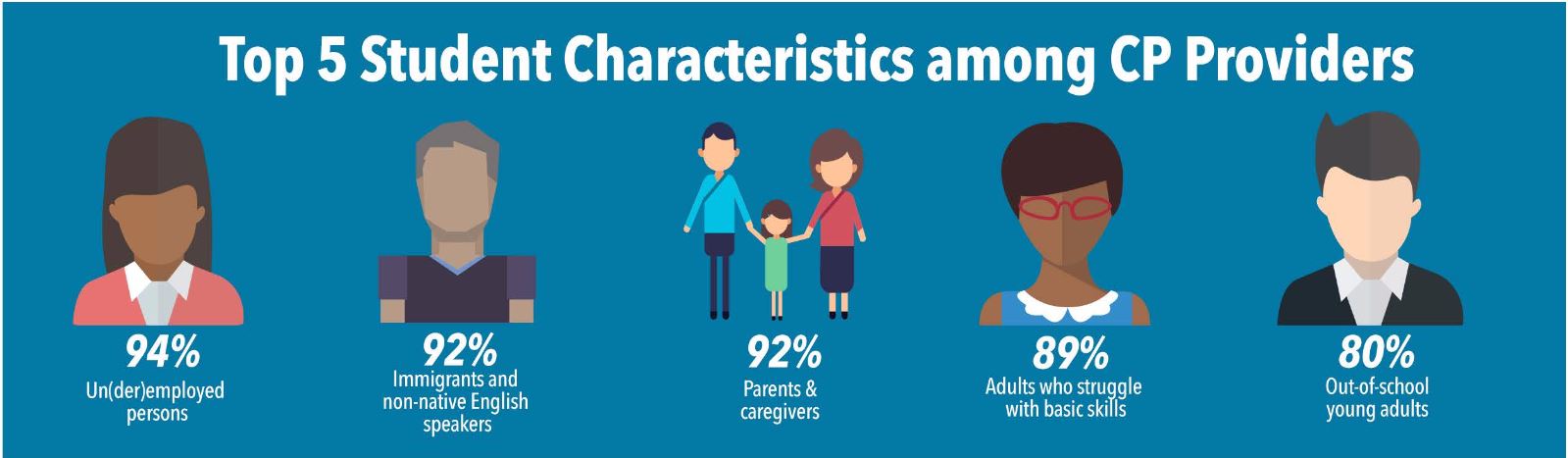

CP programs develop adults’ basic math, reading, and English language skills, while concurrently preparing them to enter postsecondary education or jobs in specific fields like healthcare or manufacturing. These programs can be run through many kinds of institutions, including community colleges, workforce development organizations, and community-based organizations. The adults seeking CP classes may vary in their skill levels, but our project focused on the adults with greatest barriers to education and employment: those who did not graduate from high school or who have low math, reading, or English language scores.

What are some of the specific concerns your practitioner partners have?

Some practitioners are concerned that requirements programs must meet may unintentionally reward programs for enrolling higher-level students—the ones who are most likely to find a job or enroll in college—rather than serving students with the greatest need. They also want to know about what non-academic supports programs may need to provide, so we are exploring the role of wraparound support services. These are important because many adult learners experience poverty and related challenges such as transportation, childcare, housing, and financial instability.

What are some of the major findings thus far?

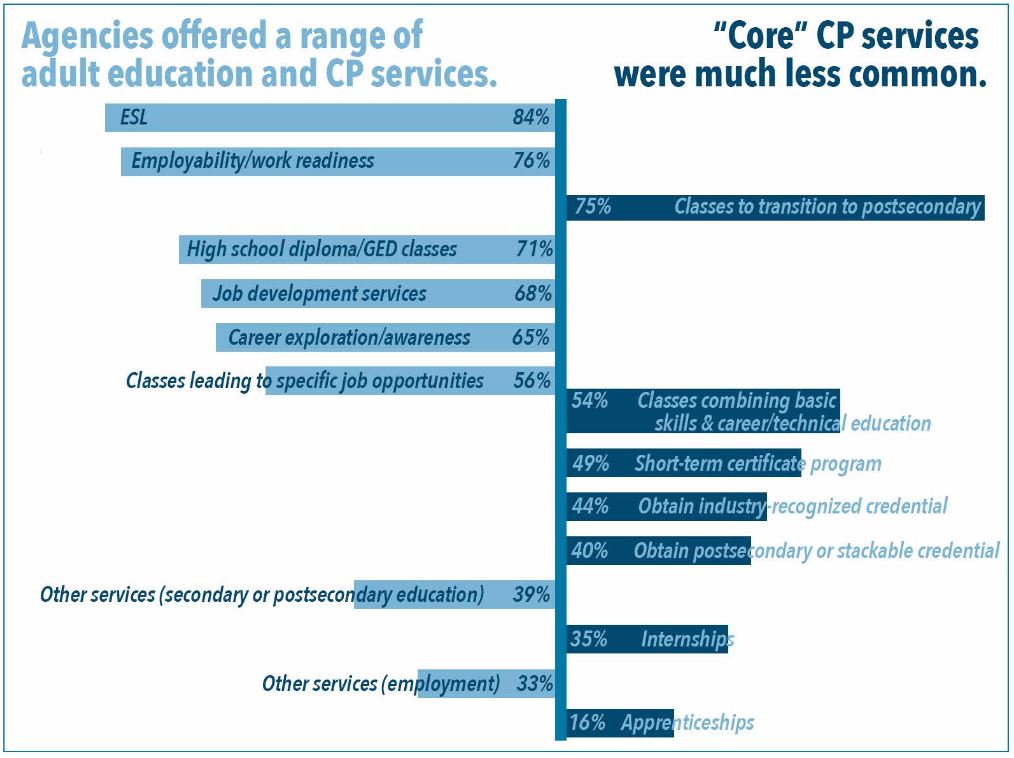

First, CP programming is widespread: more than 90% of the surveyed organizations offered or were developing CP classes in 2015. However, there are no shared program outcome measures, and this hinders comparison and documentation of programs’ collective impact. Coordination within cities primarily occurs on a small scale between a subset of organizations; citywide coordination across organizations and funding streams is less common.

Second, the majority of CP classes require students to meet minimum entry requirements such as passing a reading, math, or language test and/or possessing a high school degree. These requirements limit access for adults with the greatest barriers. To address these issues, programs are trying different options. For example, some programs offered multiple entry points (e.g., bridge classes) to enable adults with skills gaps to advance from lower-level to higher-level CP classes.

Third, agencies offer a variety of wraparound support services to meet students’ non-academic needs. Some programs bundle support services, meaning they require participation in at least two support services. These include screening for income supports and access to financial services, financial coaching and literacy, and job coaching.

The report on the survey is available online.

How are the findings being used?

Building on the findings from this study, the Chicago Citywide Literacy Coalition formed a group of 13 adult education providers to staff a Career Navigator at their local American Jobs Center to address issues such as forming shared program metrics, helping adults with lower skills, and connecting adults to support services available at the American Jobs Center.

What other issues need to be studied?

Practitioners are interested in better understanding the long-term effects and trajectories of students in CP programs. For example, they’d like to know more about postsecondary and employment outcomes and whether certain individual characteristics, program supports, or instructional approaches lead to better outcomes. Additional research could help shed light on these issues.

Meredith Larson, NCER Program Officer, interviewed Esther Prins

The figures above are from an infographic prepared by the research team and summarize the data gathered by the team.