Where Are They Now? showcases completed IES research projects. The feature describes the IES project and research findings, and updates the progress since IES project completion.

By Ed Metz, NCER Program Officer

In this inaugural Where Are They Now? feature, we take a look back at a 2008 grant to researchers at Harvard University for the development of EcoMUVE.

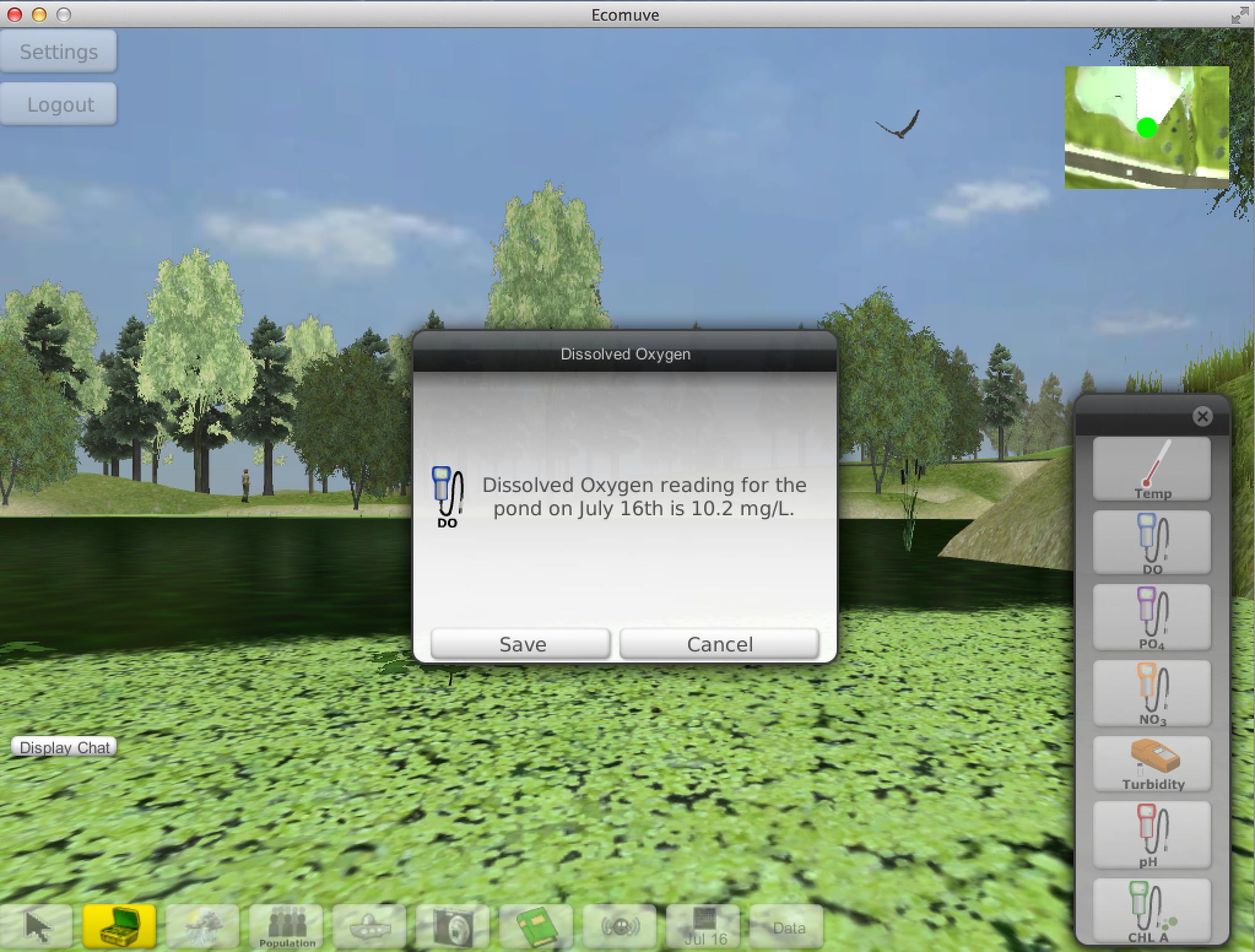

EcoMUVE uses Multi-User Virtual Environments (MUVEs), which have the look and feel of video games, to help middle school students gain a deeper understanding of ecosystems, scientific inquiry, and causal patterns. The MUVEs recreate authentic ecological settings within which students explore and collect information. Students work individually at their computers and collaborate in teams within the virtual world. EcoMUVE includes two modules, Pond and Forest; each module is a two-week inquiry-based ecosystems curriculum. EcoMUVE received the First Place award in the Interactive and Immersive Learning Category at the 2011 Association for Educational Communications and Technology conference, and has received follow-on support from the National Science Foundation and Qualcomm Wireless.

In this blog, we catch up with two of the researchers who led the development of EcoMUVE, Chris Dede and Shari Metcalf, to look back at their IES project and to learn about recent developments.

How and when did the idea to develop a virtual environment for science learning come about?

Chris Dede’s prior research with the River City project looked at supporting student inquiry using immersive exploration in a virtual world. Meanwhile, Harvard Professor Tina Grotzer was developing ways to support students in understanding complex causality in ecosystems. They worked together on a grant proposal to IES to combine their interests.

How does a virtual environment provide meaningful learning opportunities that otherwise might not be possible?

Ecosystems are complex systems shaped by relationships that often happen at microscopic levels, at a distance, and over long periods of time. Immersion in virtual environments can transform the learning experience by situating the learner in a rich simulated context in which new visualization opportunities are possible – e.g., zooming in to the microscopic level, or traveling to different points in time.

Students start to get a feel for the ecosystem and its relationships through tacit sensory clues. It is an uphill walk from the pond to the housing development, and students can walk down along a drainage ditch and through the pipe where runoff flows into the pond. The pond becomes noticeably greenish during the algae bloom.

Students can experience turbidity directly by walking under the water of the pond and seeing how murky it looks on different days.

What was an unexpected outcome of the development process?

The types of “big data” about motivation and learning for each student that EcoMUVE can generate include: time-stamped logfiles of movements and interactions in the virtual world, chat-logs of utterances, and tables of data collected and shared. Other digital tools can provide data from concept maps that chart the flow of energy through the ecosystem and that document each student team’s assertions about its systemic causal relationships, with adduced supporting evidence. Using Go-Pro cameras, students’ collaborative behaviors outside of digital media can be documented. We would like to use this data to provide near-real time feedback to students and teacher, through various forms of visualization.

What were your main research findings from the IES development project?

After using EcoMUVE, students showed gains in learning of science content, and also improvements in their attitudes towards science, particularly in the beliefs they were capable and interested in being scientists. Teachers felt that the curriculum was feasible, well-aligned with standards, and supported student engagement and learning of science content, complex causality, and inquiry, and had multiple advantages over a similar non-MUVE curriculum. A study that looked at student motivation found that, while at first students were most enthusiastic about the 3D virtual world and game-like environment, over time their engagement centered on the inquiry-based pedagogy and the collaborative problem-solving. Gains were also found in students’ complex causal reasoning about non-obvious causes; distant drivers of ecosystems dynamics and the system parameters; and processes, steady states and change over time.

How has the EcoMUVE project proceeded in recent years since the IES research project ended?

Beginning in May, 2012, we’ve been pleased to be able to offer a standalone version of the EcoMUVE software for download through a free license from Harvard University. As of January, 2015, over 1,200 users have registered with the website. The EcoMUVE project receives e-mail inquiries almost every week from educators who are interested in the curriculum. In some cases, whole districts have adopted the EcoMUVE curriculum, including Cambridge, MA, and Peoria, AZ.

Internationally, researchers at the University of Hong Kong have been working with Harvard University to use EcoMUVE for professional development, to help teachers understand how to use scientific investigations as learning activities for students. Other collaborators include Sydney University, and Aalborg University in Copenhagen.

Looking ahead, what does the future hold for EcoMUVE?

We continue to make EcoMUVE available for download from our new website, http://ecolearn.gse.harvard.edu. We have been extending our research to develop EcoMOBILE, an extension of the EcoMUVE curriculum that blends immersive virtual environments with the use of mobile technologies during field trips to real ecosystems for observations and data collection. EcoMOBILE is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Qualcomm’s Wireless Reach Initiative. We have also just started a new research project, EcoXPT, also funded through NSF, designed to work alongside EcoMUVE to support experiment-based inquiry in immersive virtual environments.

Questions? Comments? Please send them to us at IESResearch@ed.gov.

About the Interviewees

Shari J. Metcalf is Project Director of the EcoMUVE project at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She holds SB and SM degrees from MIT, and a PhD from the University of Michigan, where she designed and developed Model-It, a software tool for students building models of dynamic systems. Her professional focus is the design of educational software tools, and in particular on using modeling, simulation, and virtual immersive environments to support inquiry-based science learning.

Chris Dede is the Timothy E. Wirth Professor in Learning Technologies at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. Chris was the Principal Investigator of the EcoMUVE project. His fields of scholarship include emerging technologies, policy, and leadership. His research includes grants from NSF, IES, and the Gates Foundation to design and study immersive simulations, transformed social interactions, and online professional development.