Stakeholders in rural and high-poverty districts in Regional Educational Laboratory (REL) Appalachia’s region have noticed a troubling trend: many students graduate from high school academically well prepared but fail to enroll in college or enroll in college only to struggle and drop out within the first year. Stakeholders believe these high-performing students may face nonacademic challenges to postsecondary success, such as completing financial aid paperwork, securing transportation and housing at colleges far from home, or adjusting to campus life. To address these challenges, education leaders are looking for interventions that address nonacademic competencies: the knowledge, skills, and behaviors that enable students to navigate the social, cultural, and other implicit demands of postsecondary study.

To fill this need, REL Appalachia researchers conducted a review of the existing evidence of the impact of nonacademic interventions – that is, those designed to address nonacademic competencies – on postsecondary enrollment, persistence, and completion. The review had a particular focus on identifying interventions that also have evidence of effectiveness in communities serving students similar to those in Appalachia—high-poverty, rural students. Only one intervention, Upward Bound, demonstrated impact in rural, high-poverty communities. The review showed that Upward Bound, as implemented in the early 1990s, benefited high-poverty rural students’ college enrollment, with no demonstrated impact on persistence or completion.

Schools and communities need access to nonacademic interventions that benefit students served in high-poverty rural communities. Researchers: read on to learn more about the methods used in the evidence review, its findings, and steps you can take to support rural and high-poverty communities in improving enrollment and success in postsecondary education!

Nonacademic challenges to postsecondary success for rural students

All students face nonacademic challenges to postsecondary success, but rural populations and high-poverty populations in particular may benefit from interventions addressing those challenges because they enroll in and complete college at significantly lower rates than their nonrural or low-poverty peers. Although academic challenges contribute to this gap, rural and high-poverty populations also face unique nonacademic challenges to postsecondary enrollment and success. For example, rural students are less likely to encounter college-educated role models and high-poverty students often face inadequate college counseling at their schools (see research here, here, and here). As a result, rural and high-poverty students may have inadequate access to knowledgeable adults who can help them understand the steps needed to enroll or prepare them for the challenges of persisting in postsecondary education. Nonacademic interventions can support students in developing the knowledge, skills, and behaviors necessary to overcome these challenges and improve postsecondary enrollment and success for rural and high-poverty students.

The need for evidence-based interventions

To support decisionmakers at rural and high-poverty schools in identifying evidence-based nonacademic interventions, researchers at REL Appalachia conducted an extensive search of the published research. The search looked for rigorous studies of nonacademic interventions with evidence of positive impact on college enrollment, persistence, performance, and completion for students attending rural schools or who were identified as high poverty. The purpose of the project was to identify a suite of interventions to recommend to these education leaders.

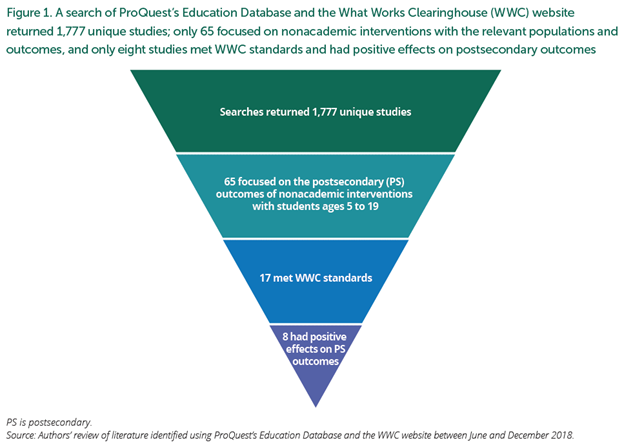

The results of our review indicate there may be gaps in the evidence available to all decisionmakers who are trying to help their students succeed in postsecondary education. The search first identified any studies that focused on postsecondary outcomes of nonacademic interventions serving students ages 5–19. Of the 1,777 studies with the relevant keywords, only 65 focused on the postsecondary outcomes of nonacademic interventions. Next, we evaluated these 65 studies against the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) design standards, which assess the quality of evaluation study designs. Only 17 studies met WWC’s rigorous study design standards with or without reservations. Finally, researchers from REL Appalachia identified studies that showed positive impacts on students overall, and studies that looked at rural students and students identified as high poverty in particular. Only eight studies showed positive, statistically significant impacts on students’ postsecondary enrollment or success overall. Of the eight studies that showed positive impacts of nonacademic interventions on postsecondary outcomes, only three focused on high-poverty populations, and only one reported specifically on rural populations.

Without additional research that focuses on low-income and rural contexts, schools and districts are left to implement programs with limited or no evidence of effectiveness. For example, the Quantum Opportunity Program (QOP) provides mentors to students as part of a long-term after school program. However, WWC reviews of QOP studies (here and here) showed indeterminate effects of the program on postsecondary outcomes. The lack of evidence should not detract from the important role QOP has in serving students, but it leaves open the question of whether those efforts are having the intended effects. With few clear alternatives, schools and districts continue to implement programs with limited evidence of effectiveness.

Action steps

Nationwide, 19 percent of U.S. public school students are enrolled in a rural school, and 24 percent are enrolled in a high-poverty school. To help districts and schools provide effective supports to those students, researchers can provide high-quality evidence on the effectiveness of nonacademic interventions in these contexts.

Carry out more studies on specific interventions designed to improve nonacademic competencies. REL Appalachia’s review found that the research on nonacademic competencies often focuses on defining the competencies themselves, rather than on studying interventions designed to develop the competencies. Of the 1,777 unique studies identified in our review, only 65 (3 percent) studied outcomes of interventions designed to improve nonacademic competencies. From these, we identified only 17 studies, representing nine interventions, with sufficiently rigorous designs to examine evidence of effectiveness.

The limited availability of rigorous evaluations of interventions suggests that, as researchers, we need to increase our focus on evaluating new interventions as they are developed or tested. Decisionmakers rarely design their own programs or interventions from scratch; they need to be able to identify existing programs and policies that are within their power to implement and have been proven effective in similar communities. Researchers can help decisionmakers select and implement successful interventions by providing evidence on whether interventions that develop students’ nonacademic competencies have positive effects on students’ postsecondary outcomes.

Design studies to generalize to rural and high-poverty populations. As researchers, we can also increase our focus on rural and high-poverty populations. REL Appalachia’s review found only three studies that focused on a high-poverty population and one that focused on a rural population. As researchers, we can address this gap in two ways: (a) we can carry out more studies specifically focused on rural and high-poverty areas; and (b) when using large national datasets or multi-site studies, we can consider rural and high-poverty populations in our sampling and disaggregate our results for these populations.

Summary

Stakeholders in rural and high-poverty contexts are looking for nonacademic interventions that will be effective with their students. To that end, REL Appalachia carried out an extensive review of evidence-based interventions. The review found few rigorous studies of nonacademic interventions, and even fewer that examined findings for students identified as high poverty or in rural settings. Without additional research, schools and districts serving rural and high-poverty populations may implement interventions that are not designed for their circumstances and may not achieve intended outcomes. As a result, resources may be wasted while rural and high-poverty students receive inadequate support for postsecondary success. In addition to investing in rigorous studies, which can take a long time to complete, researchers and practitioners can also collaborate to implement short-term research methods to identify early indicators of the success of these programs. For example, researchers may be able to support schools and districts in developing descriptive studies examining change over time or change in formative assessment outcomes.

|

Researchers have a role in helping more high school graduates from rural communities enroll, persist, and succeed in postsecondary education.

|

Rural and high-poverty schools and districts have unique strengths and challenges, and the lack of information about how interventions perform in those contexts presents a dilemma for decisionmakers: do nothing, or else muddle through with existing evidence, investing in interventions that don’t address local needs. As researchers, we can help resolve this dilemma by providing rigorous evidence about effective interventions tailored to rural and high-poverty contexts, as well as supporting practitioners in using more accessible methods to investigate the short-term outcomes of the programs they are already implementing.

by Rebecca A. Schmidt and CJ Park, Regional Educational Laboratory Appalachia