The Institute of Education Sciences funds and supports Researcher-Practitioner Partnerships (RPP) that address significant challenges in education. In this guest blog post, Karen D. Thompson, of Oregon State University and Josh Rew, Martha Martinez, and Chelsea Clinton, of the Oregon Department of Education, describe the work their RPP is doing to better understand and improve the performance English learners in Oregon. Click here to learn more about RPP grants. This research will be part of a Regional Educational Laboratory webinar on June 21.

According to the most recent data, about 10 percent of K-12 students in U.S. public schools were classified as English learners (EL). But that only tells part of the story: a large proportion of students in U.S. schools are former ELs, who have attained proficiency in English and “exited” EL services. Currently, in most states and the nation, we do not know the size of the former EL group because states have only been required to monitor this group of students for a limited amount of time.

Education agencies and the media routinely report the achievement gap between current EL students and their non-EL peers. However, analyzing outcomes only for current EL students does not provide a complete picture of how well schools are serving the full group of students who entered school not yet proficient in English. We refer to this full group, which includes both current and former ELs, as Ever English Learners (Ever ELs).

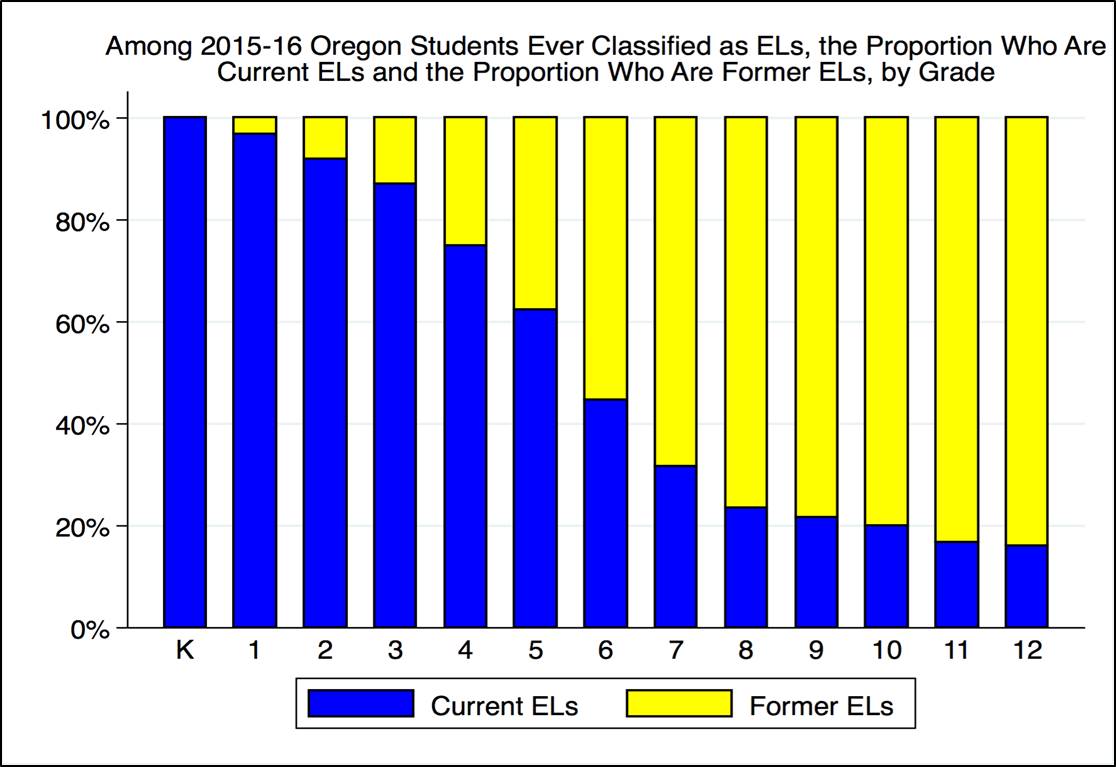

Through our IES-funded partnership, the Oregon Department of Education (ODE) and Oregon State University (OSU) has identified the full group of both current and former ELs in Oregon public K-12 schools. Using 2015-16 Oregon data, we looked at the proportion of Ever ELs who are current and former ELs at each grade level. As seen in Figure 1 below, former ELs outnumber current ELs in grades 6 and above, with the relative size of the former EL population increasing at each grade level.

Figure 1

Starting with the 2012-13 school year, ODE began annually reporting to the public the outcomes of Ever ELs (e.g., achievement and growth, chronic absenteeism, rates of freshmen on-track, and graduation rates). These annual reports include school and district report cards, the statewide report card, and technical reports corresponding to specific state initiatives, such as graduation rates, chronic absenteeism, assessment participation, and district EL accountability.

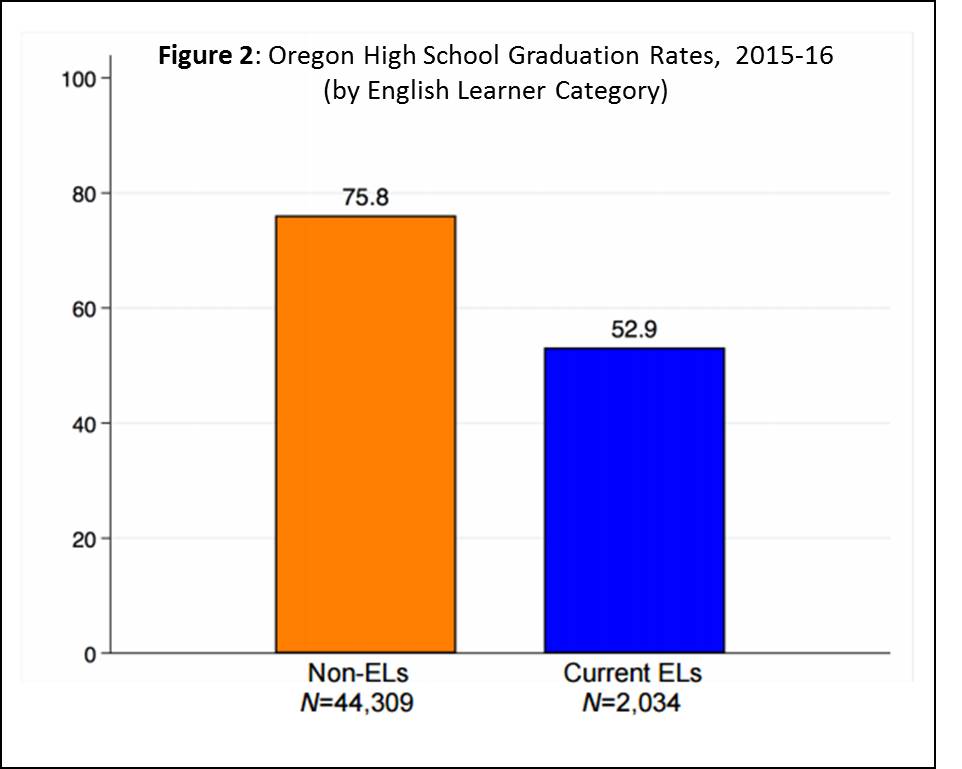

In the past, states have typically reported achievement outcomes for students currently classified as ELs and compared these to outcomes for all students not currently classified as ELs. Under this reporting scheme, the non-EL subgroup consists of students never classified as ELs and former ELs. With this grouping (Figure 2), graduation rates for ELs appear much lower than graduation rates for non-ELs (52.9 percent for ELs compared to 75.8 percent for non-ELs).

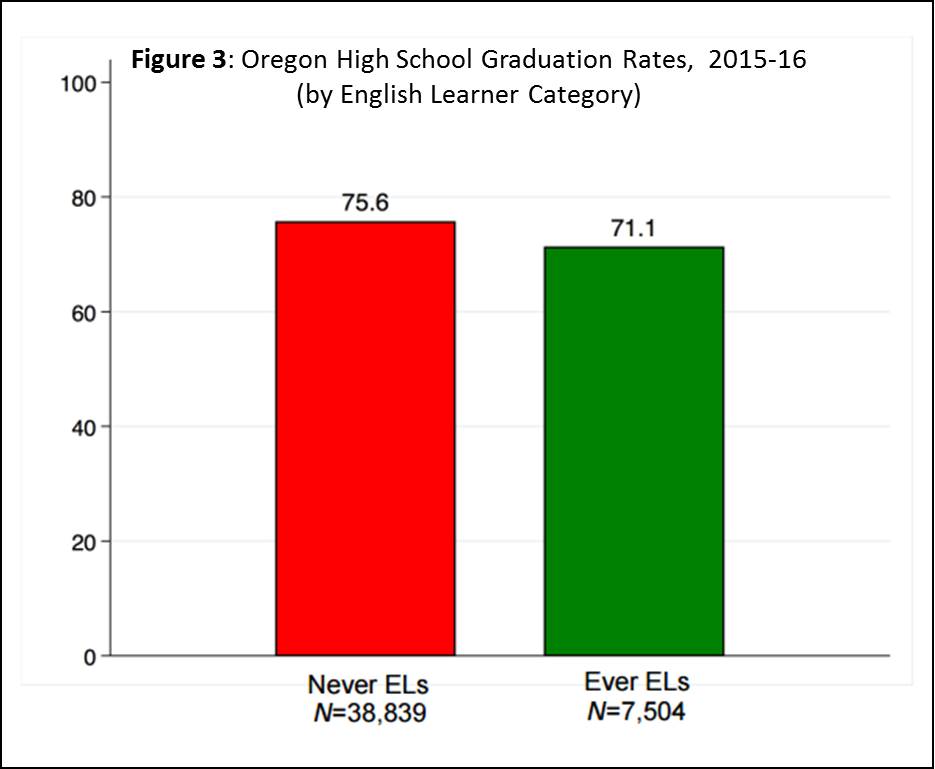

However, it may be more appropriate in some situations to instead analyze outcomes for the full group of students who entered school as ELs (Figure 3). Under this alternative reporting scheme, if we combine outcomes for both current and former ELs to create the Ever EL group, we see that graduation rates for Ever ELs are much closer to graduation rates for students never classified as ELs (71.1 percent for Ever ELs compared to 75.6 percent for Never ELs).

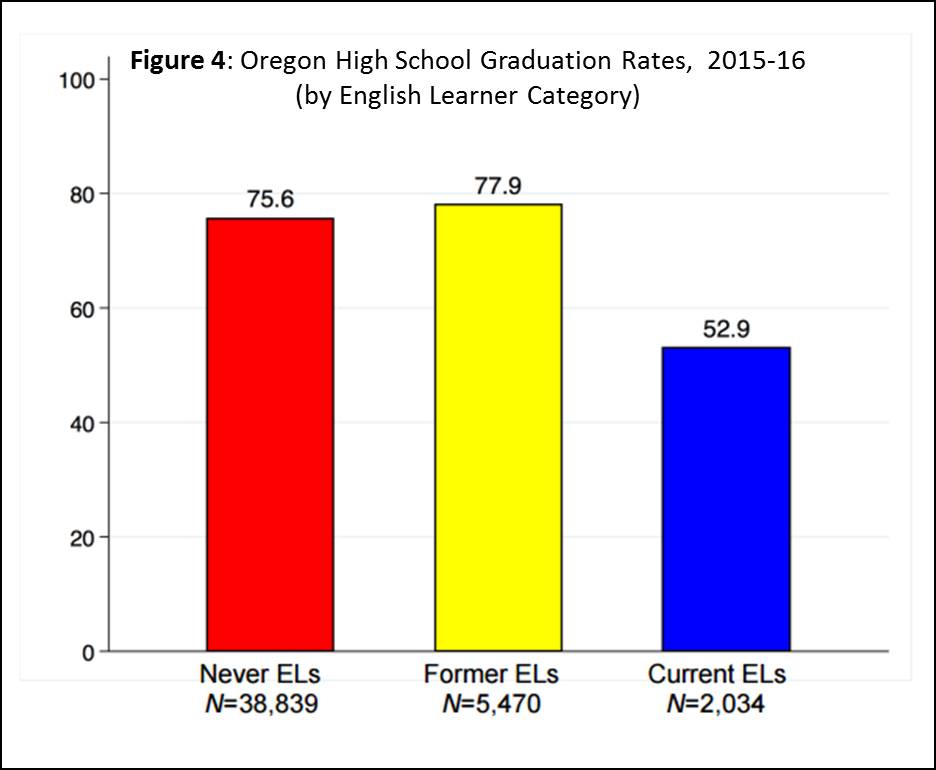

While the low graduation rates for current ELs are certainly concerning, it is also important to know that former ELs are graduating at rates slightly higher than students never classified as ELs (77.9 percent vs. 75.6 percent, respectively), as shown in Figure 4.

This is particularly noteworthy since former ELs represent a larger proportion of the student population than current ELs at the secondary level.

In addition to annual reporting, the ODE began using data for Ever ELs in 2015-16 to identify districts in need of support, assistance, and improvement, as required by state law. The state’s accountability system identifies the districts with the highest needs and lowest outcomes as measured by demographic indicators (such as economically disadvantage, migrant or homeless status) and outcome data (e.g., growth, graduation, and post-secondary enrollment) for Ever ELs. Identified districts conduct a needs assessment, identify evidence-based and culturally responsive technical assistance, develop a technical assistance implementation plan, monitor progress, and review outcomes and make necessary adjustments. Along with its applications for reporting and accountability, we have used the Ever EL framework to analyze special education disproportionality, documenting implications for research, policy, and practice.

To learn more about how education agencies are using the Ever EL category, join us and colleagues from New York City for a June 21 webinar, sponsored by Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast and Islands.