In January 2022, NCES released the rescaled data files for three adult literacy assessments conducted several decades earlier: the 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), the 1994 International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), and the 2003 Adult Literacy and Lifeskills Survey (ALL). By connecting the rescaled data from these assessments with data from the current adult literacy assessment, the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), researchers can examine trends on adult skills in the United States going back to 1992. This blog post traces the history of each of these adult literacy assessments, describes the files and explains what “rescaling” means, and discusses how these files can be used in analyses in conjunction with the PIAAC files. The last section of the post offers several example analyses of the data.

A Brief History of International and National Adult Literacy Assessments Conducted in the United States

The rescaled data files highlighted in this blog post update and combine historical data from national and international adult literacy studies that have been conducted in the United States.

NALS was conducted in 1992 by NCES and assessed U.S. adults in households, as well as adults in prisons. IALS—developed by Statistics Canada and ETS in collaboration with 22 participating countries, including the United States—assessed adults in households and was administered in three waves between 1994 and 1998. ALL was administered in 11 countries, including the United States, and assessed adults in two waves between 2003 and 2008.

PIAAC seeks to ensure continuity with these previous surveys, but it also expands on their quality assurance standards, extends the definitions of literacy and numeracy, and provides more information about adults with low levels of literacy by assessing reading component skills. It also, for the first time, includes a problem-solving domain to emphasize the skills used in digital (originally called “technology-rich”) environments.

How Do the Released Data Files From the Earlier Studies of Adult Skills Relate to PIACC?

All three of the released restricted-use data files (for NALS, IALS, and ALL) relate to PIAAC, the latest adult skills assessment, in different ways.

The NALS data file contains literacy estimates and background characteristics of U.S. adults in households and in prisons in 1992. It is comparable to the PIAAC data files for 2012/14 and 2017 through rescaling of the assessment scores and matching of the background variables to those of PIAAC.

The IALS and ALL data files contain literacy (IALS and ALL) and numeracy (ALL) estimates and background characteristics of U.S. adults in 1994 (IALS) and 2003 (ALL). Similar to NALS, they are comparable to the PIAAC restricted-use data (2012/14) through rescaling of the literacy and numeracy assessment scores and matching of the background variables to those of PIAAC. These estimates are also comparable to the international estimates of skills of adults in several other countries, including in Canada, Hungary, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, and New Zealand (see the recently released Data Point International Comparisons of Adult Literacy and Numeracy Skills Over Time). While the NCES datasets contain only the U.S. respondents, IALS and ALL are international studies, and the data from other participating countries can be requested from Statistics Canada (see the IALS Data Files/Publications and ALL Data pages for more detail). See the History of International and National Adult Literacy Assessments page for additional background on these studies.

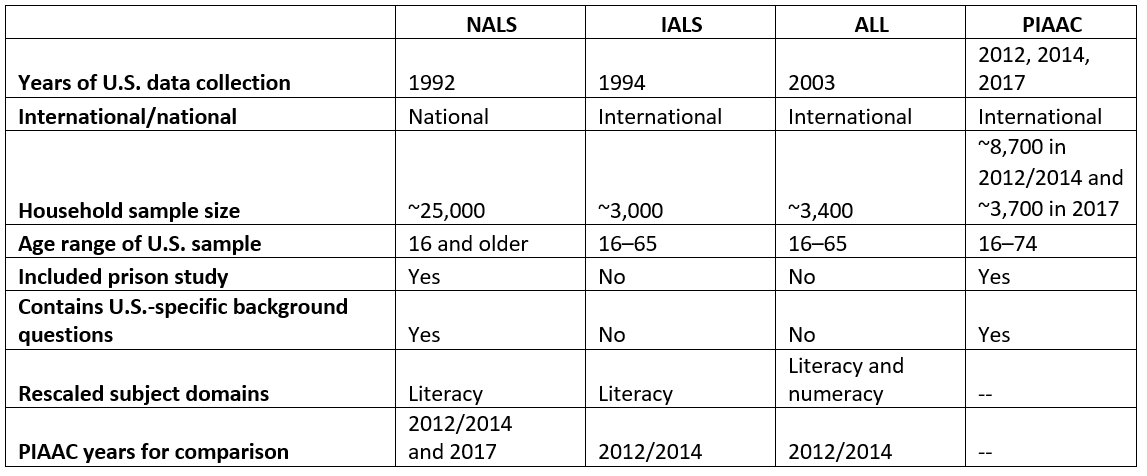

Table 1 provides an overview of the rescaled NALS, IALS, and ALL data files.

Table 1. Overview of the rescaled data files for the National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), and Adult Literacy and Lifeskills Survey (ALL)

What Does “Rescaled” Mean?

“Rescaling” the literacy (NALS, IALS, ALL) and numeracy (ALL) domains from these three previous studies means that the domains were put on the same scale as the PIAAC domains through the derivation of updated estimates of proficiency created using the same statistical models used to create the PIAAC skills proficiencies. Rescaling was possible because PIAAC administered a sufficient number of the same test questions used in NALS, IALS, and ALL.1 These rescaled proficiency estimates allow for trend analysis of adult skills across the time points provided by each study.

What Can These Different Files Be Used For?

While mixing the national and international trend lines isn’t recommended, both sets of files have their own distinct advantages and purposes for analysis.

National files

The rescaled NALS 1992 files can be used for national trend analyses with the PIAAC national trend points in 2012/2014 and 2017. Some potential analytic uses of the NALS trend files are to

- Provide a picture of the skills of adults only in the United States;

- Examine the skills of adults in prison and compare their skills with those of adults in households over time, given that NALS and PIAAC include prison studies conducted in 1992 and 2014, respectively;

- Conduct analyses on subgroups of the population (such as those ages 16–24 or those with less than a high school education) because the larger sample size of NALS allows for more detailed breakdowns along with the U.S. PIAAC sample;

- Focus on the subgroup of older adults (ages 66–74), given that NALS sampled adults over the age of 65, similar to PIAAC, which sampled adult ages 16–74; and

- Analyze U.S.-specific background questions (such as those on race/ethnicity or health-related practices).

International files

The rescaled IALS 1994 and ALL 2003 files can be used for international trend analyses among six countries with the U.S. PIAAC international trend point in 2012/2014: Canada, Hungary, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. Some potential analytic uses of the IALS and ALL trend files are to

- Compare literacy proficiency results internationally and over time using the results from IALS, ALL, and PIAAC; and

- Compare numeracy proficiency results internationally and over time using the results from ALL and PIAAC.

Example Analyses Using the U.S. Trend Data on Adult Literacy

Below are examples of a national trend analysis and an international trend analysis conducted using the rescaled NALS, IALS, and ALL data in conjunction with the PIAAC data.

National trend estimates

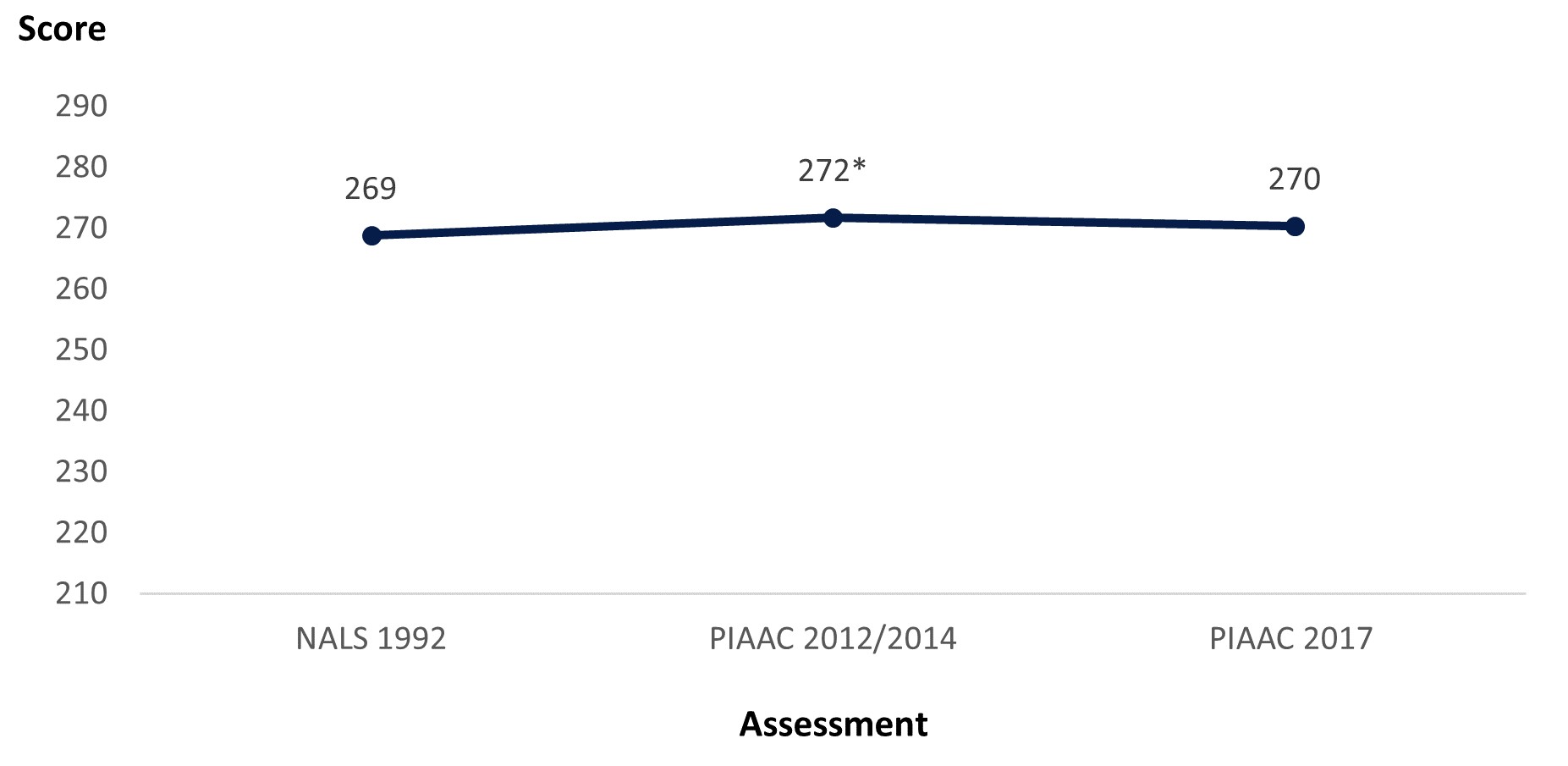

The literacy scores of U.S. adults increased from 269 in NALS 1992 to 272 in PIAAC 2012/2014. However, the PIAAC 2017 score of 270 was not significantly different from the 1992 or 2012/2014 scores.

Figure 1. Literacy scores of U.S. adults (ages 16–65) along national trend line: Selected years, 1992–2017

* Significantly different (p < .05) from NALS 1992 estimate.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Adult Literacy Survey (NALS), NALS 1992; and Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), PIAAC 2012–17.

International trend estimates

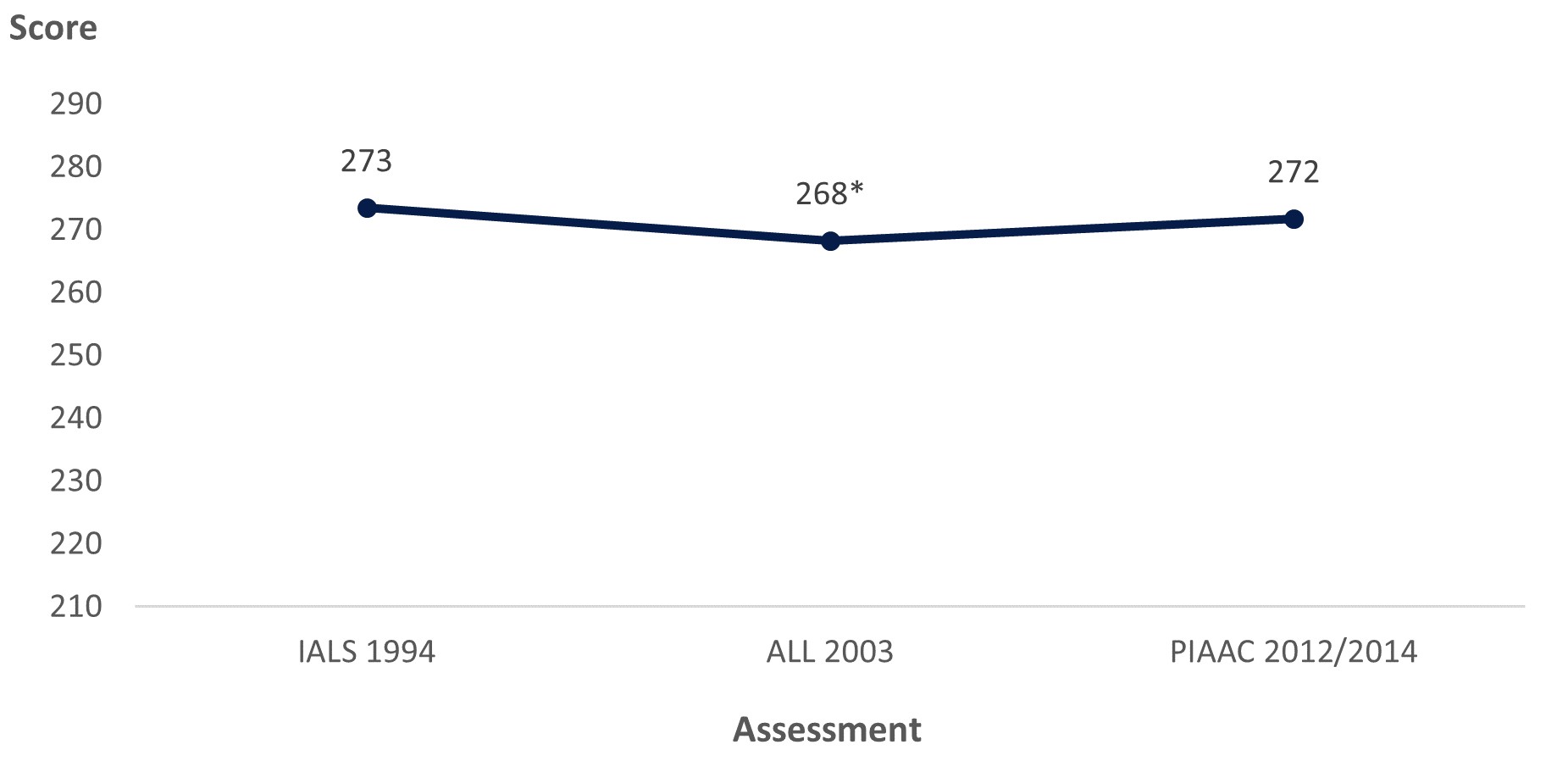

The literacy scores of U.S. adults decreased from 273 in IALS 1994 to 268 in ALL 2003 before increasing to 272 in PIAAC 2012/2014. However, the PIAAC 2012/2014 score was not significantly different from the IALS 1994 score.

Figure 2. Literacy scores of U.S. adults (ages 16–65) along international trend line: Selected years, 1994–2012/14

* Significantly different (p < .05) from IALS 1994 estimate.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS), 1994–98; Adult Literacy and Lifeskills Survey (ALL), 2003–08; and Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), PIAAC 2012/14. See figure 1 in the International Comparisons of Adult Literacy and Numeracy Skills Over Time Data Point.

How to Access the Rescaled Data Files

More complex analyses can be conducted with the NALS, IALS, and ALL rescaled data files. These are restricted-use files and researchers must obtain a restricted-use license to access them. Further information about these files is available on the PIAAC Data Files page (see the “International Trend Data Files and Data Resources” and “National Trend Data Files and Data Resources” sections at the bottom of the page).

Additional resources:

By Emily Pawlowski, AIR, and Holly Xie, NCES

[1] In contrast, the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), another assessment of adult literacy conducted in the United States, was not rescaled for trend analyses with PIAAC. For various reasons, including the lack of overlap between the NAAL and PIAAC literacy items, NAAL and PIAAC are thought to be the least comparable of the adult literacy assessments.