NCES recently released revised Common Core of Data (CCD) Preliminary Files, which are the product of the school year (SY) 2020–21 CCD data collection. CCD, the Department of Education’s primary database on public elementary and secondary education in the United States, provides comprehensive annual data on enrollment, school finances, and student graduation rates.

Here are a few key takeaways from the newly released data files:

Public school enrollment in SY 2020–21 was lower than it was in SY 2019–20.

Overall, the number of students enrolled in public schools decreased by 3 percent from SY 2019–20 to SY 2020–21. Note that Illinois did not submit data in time to be included in this preliminary report. The SY 2019–20 and SY 2020–21 total enrollment counts for California, Oregon, American Samoa, and the Bureau of Indian Education do not include prekindergarten counts.

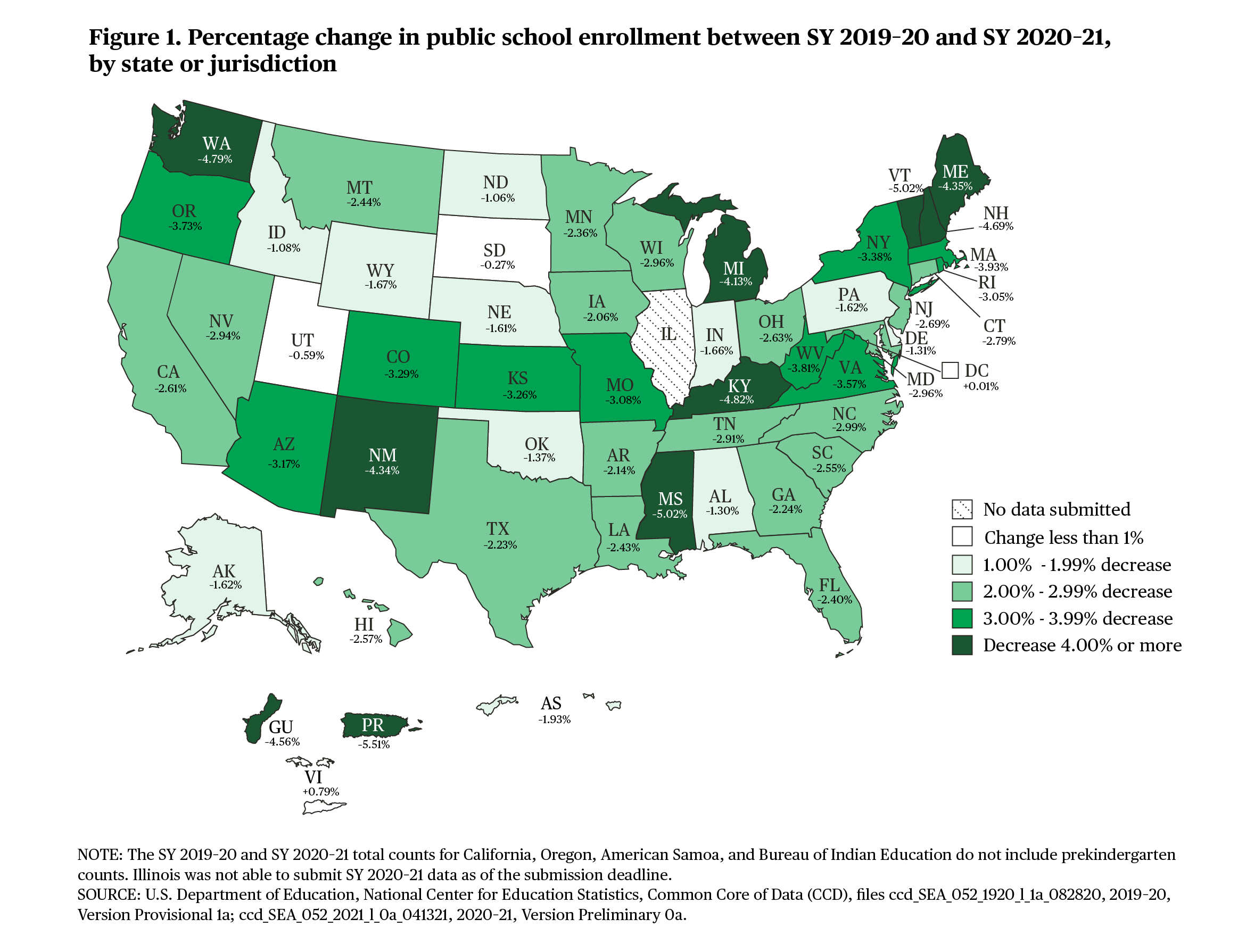

The rate of decline in public school enrollment in SY 2020–21 was not consistent across all states.

Within states, the largest decreases were in Mississippi and Vermont (5 percent each), followed by Washington, New Mexico, Kentucky, New Hampshire, and Maine (each between 4 and 5 percent) (figure 1). Eighteen states had decreases of 3 percent or more; 29 states had decreases between 1 and 3 percent; and the District of Columbia, South Dakota, and Utah had changes of less than 1 percent.

Lower grade levels experienced a greater rate of decline in public school enrollment than did higher grade levels in SY 2020–21.

Public school enrollment decreased by 13 percent for prekindergarten and kindergarten and by 3 percent for grades 1–8. Public school enrollment increased by 0.4 percent for grades 9–12.

Most other jurisdictions experienced declines in public school enrollment in SY 2020–21.

Public school enrollment decreased in Puerto Rico (6 percent), Guam (5 percent), and American Samoa (2 percent). The Virgin Islands, however, experienced an increase of less than 1 percent.

To access the CCD preliminary data files and learn more about public school enrollment in SY 2020–21, visit the CCD data files webpage.