By Sarah Souders

More than 3,915,918 individuals were employed by degree-granting postsecondary institutions in 2015. These employees provided services and support to the 19,977,270 students attending the nation’s 4,562 degree-granting institutions.

We know this information—and much more—because of the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), a program in the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). In fact, these data points only scratch the surface of information collected and updated annually by IPEDS. Each year, IPEDS issues 12 surveys to all postsecondary institutions receiving Title IV Federal Aid[1] and some institutions that participate by choice. The surveys provide data on a broad range of topics, from enrollment, admissions, and cost to grad rates, faculty, and human resources. These data are reported by gender, race/ethnicity, institution type, and more.

But we don’t just want people to know about the data – we want them to use it!

The “Use the Data” landing page (see image below) provides many options for analysis. Users can look up and compare institutions, view trends and statistical tables for specific data points, download a complete survey file, customize a data file, or download a report summarizing the data for specific institutions.

There are many options for analysis given the extensive data collection and number of tools. One tool, the IPEDS Trend Generator, allows users to select a subject and question to observe trends over time. The trend generator allows users to explore enrollment trends, among many other topics.

Below is an example of a bar graph that can be generated using this tool. With the click of a couple of buttons, you can quickly learn that the number of students attending postsecondary institutions (as measured by 12-month enrollment) has been declining in recent years, after peaking in 2010-11 at 29,522,688 students. By 2014-15, enrollment decreased to 27,386,275 students, a decline of more than 2 million students.

In addition to producing graphical displays, data from the Trend Generator can quickly be exported to an Excel file.

Users also have the option to create custom data files which can be exported to Excel, SAS, STATA, or SPSS files. Users can choose individual or specific institutions using their own criteria, or groups of similar institutions can be selected at once by using predetermined categorizations. Some pre-set groupings include whether the institution is the state’s land grant institution, a Historically Black College and University, or a tribal college. Institutional groupings can also be selected by geographic characteristics and other groupings, such as highest degree offered, availability of distance education, and Carnegie classification. The full list of institutional groupings can be found on the IPEDS website.

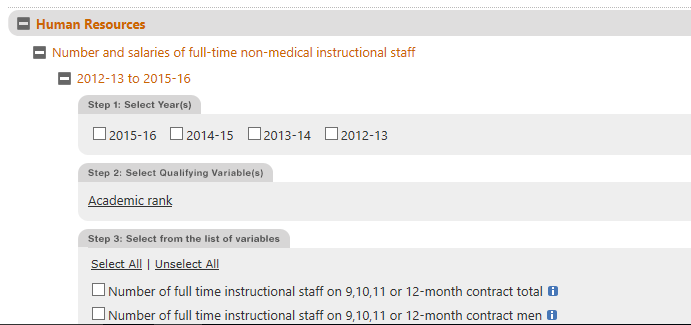

After selecting the institutions, users can choose the variables to be analyzed. In the screenshot below, you can see that the variable “number and salaries of non-medical full-time staff” allows users to select breakouts by academic rank, such as professor, associate professor, lecturer, etc. These breakouts can provide greater detail with regard to current and average salary. Once the variables are selected, the desired data file is complete and can be exported into one of the available formats.

The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System contains a multitude of data which can be accessed for all levels of analysis, whether you are an experienced statistician or just a casual user. If you are using the data and have questions or comments, contact the IPEDS Help Desk by phone at 1-877-225-2568 or by email: ipedshelp@rti.org .

Sarah Souders was a 2017 summer intern for NCES. She is a student at The Ohio State University.

[1] Title IV of the HEA authorizes the federal government’s primary student aid programs, which are the major source of federal support to postsecondary students. Title IV aid includes programs like Pell Grants, Stafford Loans, Perkins Loans, Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants, and Federal Work Study. If an institution accepts aid from programs authorized by Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended (20 USC 1094, Section 487(a)(17) and 34 CFR 668.14(b)(19)), then they are required to complete all IPEDS surveys.