Dear reader,

You’ve been asked to participate in a study.

. . . I know what you’re thinking. Oh, great. Another request for my time. I am already so busy.

Hmm, if I participate, what is my information going to be used for? Well, the letter says that collecting data from me will help researchers study education, and it says something else about how the information I provide would “inform education policy . . .”

But what does that mean?

If you’re a parent, student, teacher, school administrator, or district leader, you may have gotten a request like this from me or a colleague at the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). NCES is one of 13 federal agencies that conducts survey and assessment research in order to help federal, state, and local policymakers better understand public needs and challenges. It is the U.S. Department of Education’s (ED’s) statistical agency and fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report statistics on the condition of American education. The law also directs NCES to do the same about education across the globe.

But how does my participation in a study actually support the role Congress has given NCES?

Good question. When NCES conducts a study, participants are asked to provide information about themselves, their students or child/children, teachers, households, classrooms, schools, colleges, or other education providers. What exactly you will be asked about is based on many considerations, including previous research or policy needs. For example, maybe a current policy might be based on results from an earlier study, and we need to see if the results are still relevant. Maybe the topic has not been studied before and data are needed to determine policy options. In some cases, Congress has charged NCES with collecting data for them to better understand education in general.

Data collected from participants like you are combined so that research can be conducted at the group level. Individual information is not the focus of the research. Instead, NCES is interested in the experiences of groups of people or groups of institutions—like schools—based on the collected data. To protect respondents, personally identifiable information like your name (and other information that could identify you personally) is removed before data are analyzed and is never provided to others. This means that people who participate in NCES studies are grouped in different ways, such as by age or type of school attended, and their information is studied to identify patterns of experiences that people in these different groups may have had.

Let’s take a look at specific examples that show how data from NCES studies provide valuable information for policy decisions.

When policymakers are considering how data can inform policy—either in general or for a specific law under consideration—data from NCES studies play an important role. For example, policymakers concerned that students in their state/district/city often struggle to pay for college may be interested in this question:

“What can education data tell me about how to make college more affordable?”

Or policymakers further along in the law development process might have more specific ideas about how to help low-income students access college. They may have come across research linking programs such as dual enrollment—when high school students take college courses—to college access for underrepresented college students. An example of this research is provided in the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) dual-enrollment report produced by ED’s Institute for Education Sciences (IES), which shows that dual-enrollment programs are effective at increasing students’ access to and enrollment in college and attainment of degrees. This was found to be the case especially for students typically underrepresented in higher education.

Then, these policymakers might need more specific questions answered about these programs, such as:

“What is the benefit of high school students from low-income households also taking college courses?”

Thanks to people who participate in NCES studies, we have the data to address such policy questions. Rigorous research using data from large datasets, compiled from many participants, can be used to identify differences in outcomes between groups. In the case of dual-enrollment programs, college outcomes for dual-enrollment participants from low-income households can be compared with those of dual-enrollment participants from higher-income households, and possible causes of those differences can be investigated.

The results of these investigations may then inform enactment of laws or creation of programs to support students. In the case of dual enrollment, grant programs might be set up at the state level for districts and schools to increase students’ local access to dual-enrollment credit earning.

This was very close to what happened in 2012, when I was asked by analysts in ED’s Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development to produce statistical tables with data on students’ access to career and technical education (CTE) programs. Research, as reviewed in the WWC dual-enrollment report, was already demonstrating the benefits of dual enrollment for high school students. Around 2012, ED was considering a policy that would fund the expansion of dual enrollment specifically for CTE. The reason I was asked to provide tables on the topic was my understanding of two important NCES studies, the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002) and the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (HSLS:09). Data provided by participants in those studies were ideal for studying the question. The tables were used to evaluate policy options. Based on the results, ED, through the President, made a budget request to Congress to support dual-enrollment policies. Ultimately, dual-enrollment programs were included in the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (Perkins V).

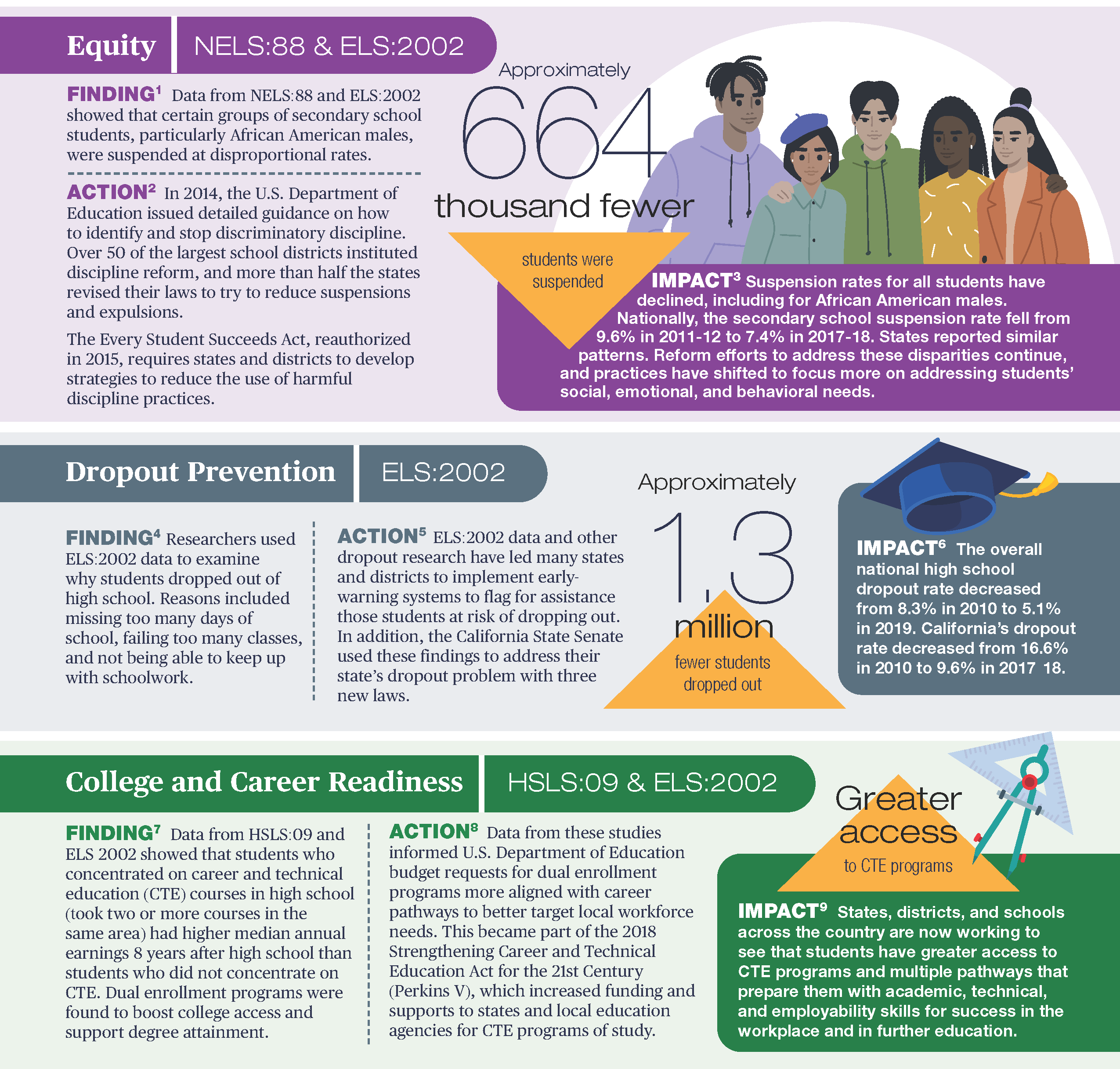

The infographic below shows that this scenario—in which NCES data provided by participants like you were used to provide information about policy—has happened on different scales for different policies many times over the past few decades. The examples included are just some of those from the NCES high school longitudinal studies. NCES data have been used countless times in its 154-year history to improve education for American students. Check out the full infographic (PDF) with other examples.

However, it’s not always the case that a direct line can be drawn between data from NCES studies and any one policy. Research often informs policy indirectly by educating policymakers and the public they serve on critical topics. Sometimes, as in the dual-enrollment and CTE programs research question I investigated, it can take time before policy gets enacted or a new program rolls out. This does not lessen the importance of the research, nor the vital importance of the data participants provide that underpin it.

The examples in the infographic represent experiences of actual individuals who took the time to tell NCES about themselves by participating in a study.

If you are asked to participate in an NCES study, please consider doing so. People like you, schools like yours, and households in your town do matter—and by participating, you are helping to inform decisions and improve education across the country.

By Elise Christopher, NCES