By Michael Frye and Sarah Costelloe. Both are part of Abt Associates team working on the What Works Clearinghouse.

Technology is part of almost every aspect of college life. Colleges use technology to improve student retention, offer active and engaging learning, and help students become more successful learners. The What Works Clearinghouse’s latest practice guide, Using Technology to Support Postsecondary Student Learning, offers several evidence-based recommendations to help higher education instructors, instructional designers, and administrators use technology to improve student learning outcomes.

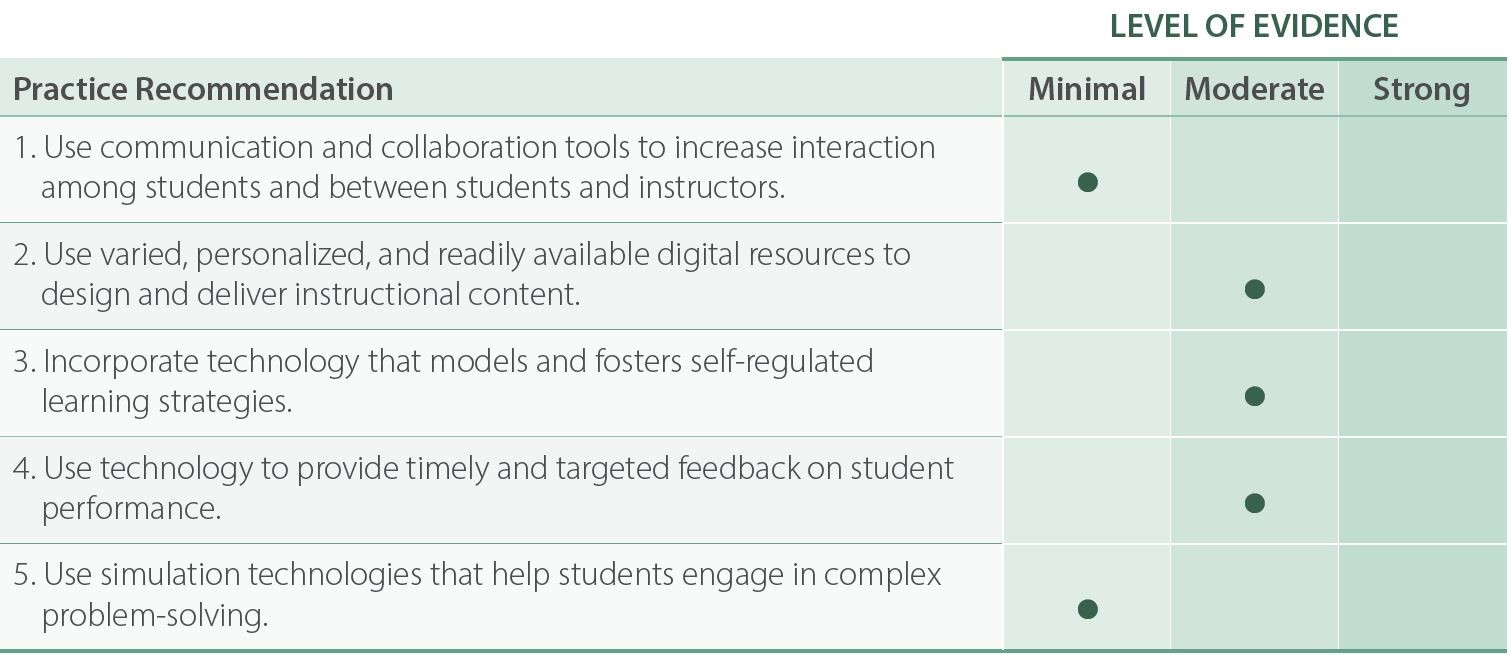

IES practice guides incorporate research, practitioner experience, and expert opinions from a panel of nationally recognized experts. The panel that developed Using Technology to Support Postsecondary Student Learning included five experts with many years of experience leading the adoption, use, and research of technology in postsecondary classrooms. Together, guided by Abt Associates’ review of the rigorous research on the topic, the Using Technology to Support Postsecondary Student Learning offers five evidence-based recommendations:

Each recommendation is assigned an evidence level of minimal, moderate, or strong. The level of evidence reflects how well the research demonstrates the effectiveness of the recommended practices. For an explanation of how levels of evidence are determined, see the Practice Guide Level of Evidence Video. The evidence-based recommendations also include research-based strategies and examples for implementation in postsecondary settings. Together, the recommendations highlight five interconnected themes that the practice guide’s authors suggest readers consider:

- Focus on how technology is used, not on the technology itself.

“The basic act of teaching has actually changed very little by the introduction of technology into the classroom,” said panelist MJ Bishop, “and that’s because simply introducing a new technology changes nothing unless we first understand the need it is intended to fill and how to capitalize on its unique capabilities to address that need.” Because technology evolves rapidly, understanding specific technologies is less important than understanding how technology can be used effectively in college settings. “By understanding how a learning outcome can be enhanced and supported by technologies,” said panelist Jennifer Sparrow, “the focus stays on the learner and their learning.”

- Technology should be aligned to specific learning goals.

Every recommendation in this guide is based on one idea: finding ways to use technology to engage students and enhance their learning experiences. Technology can engage students more deeply in learning content, activate their learning processes, and provide the social connections that are key to succeeding in college and beyond. To do this effectively, any use of technology suggested in this guide must be aligned with learning goals or objectives. “Technology is not just a tool,” said Panel Chair Nada Dabbagh. “Rather, technology has specific affordances that must be recognized to use it effectively for designing learning interactions. Aligning technology affordances with learning outcomes and instructional goals is paramount to successful learning designs.”

- Pay attention to potential issues of accessibility.

The Internet is ubiquitous, but many households—particularly low-income households and those of recent immigrants and in rural communities—may not be able to afford or otherwise access digital communications. Course materials that rely heavily on Internet access may put these students at a disadvantage. “Colleges and universities making greater use of online education need to know who their students are and what access they have to technology,” said panelist Anthony Picciano. “This practice guide makes abundantly clear that colleges and universities should be careful not to be creating digital divides.”

Instructional designers must also ensure that learning materials on course websites and course/learning management systems can accommodate students who are visually and/or hearing impaired. “Technology can greatly enhance access to education both in terms of reaching a wide student population and overcoming location barriers and in terms of accommodating students with special needs,” said Dabbagh. “Any learning design should take into consideration the capabilities and limitations of technology in supporting a diverse and inclusive audience.”

- Technology deployments may require significant investment and coordination.

Implementing any new intervention takes training and support from administrators and teaching and learning centers. That is especially true in an environment where resources are scarce. “In reviewing the studies for this practice guide,” said Picciano, “it became abundantly clear that the deployment of technology in our colleges and universities has evolved into a major administrative undertaking. Careful planning that is comprehensive, collaborative, and continuous is needed.”

“Hardware and software infrastructure, professional development, academic and student support services, and ongoing financial investment are testing the wherewithal of even the most seasoned administrators,” said Picciano. “Yet the dynamic and changing nature of technology demands that new strategies be constantly evaluated and modifications made as needed.”

These decisions are never easy. “Decisions need to be made,” said Sparrow, “about investment cost versus opportunity cost. Additionally, when a large investment in a technology has been made, it should not be without investment in faculty development, training, and support resources to ensure that faculty, staff, and students can take full advantage of it.”

- Rigorous research is limited and more is needed.

Despite technology’s ubiquity in college settings, rigorous research on the effects of technological interventions on student outcomes is rather limited. “It’s problematic,” said Bishop, “that research in the instructional design/educational technology field has been so focused on things, such as technologies, theories, and processes, rather than on the problems we’re trying to solve with those things, such as developing critical thinking, enhancing knowledge transfer, and addressing individual differences. It turns out to be very difficult to cross-reference the instructional design/educational technology literature with the questions the broader field of educational research is trying to answer.”

More rigorous research is needed on new technologies and how best to support instructors and administrators in using them. “For experienced researchers as well as newcomers,” said Picciano, “technology in postsecondary teaching and learning is a fertile ground for further inquiry and investigation.”

Readers of this practice guide are encouraged to adapt the advice provided to the varied contexts in which they work. The five themes discussed above serve as a lens to help readers approach the guide and decide whether and how to implement some or all of the recommendations.

Download Using Technology to Support Postsecondary Student Learning from the What Works Clearinghouse™ website at https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide/25.