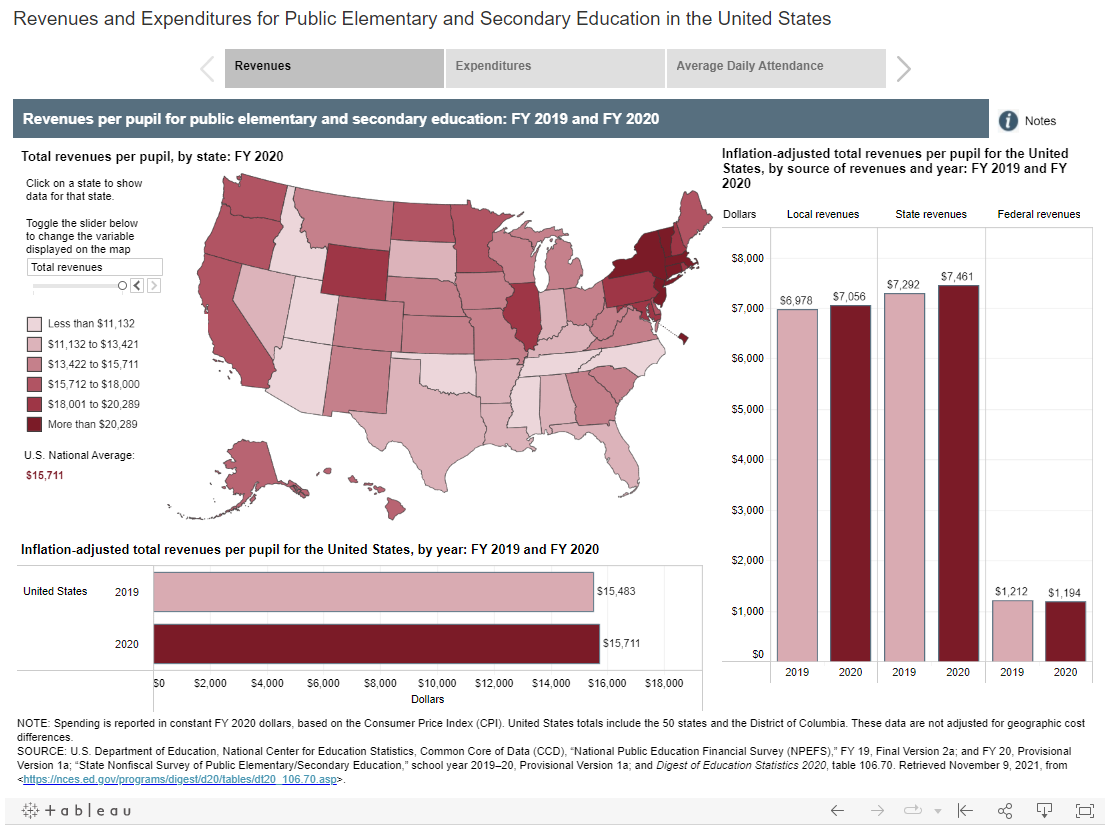

To accompany the recently released Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education FY 2020, NCES has created an interactive data visualization tool to highlight the per pupil revenues and expenditures (adjusted for inflation) and average daily attendance (ADA) trends from the fiscal year (FY) 2020 National Public Education Financial Survey.

This tool allows users to see national or state-specific per pupil amounts and year-to-year percentage changes for both total revenue and current expenditures by using a slider to toggle between the two variables. Total revenues are shown by source, and total current expenditures are shown by function and subfunction. Clicking on a state in the map will display data for the selected state in the bar charts.

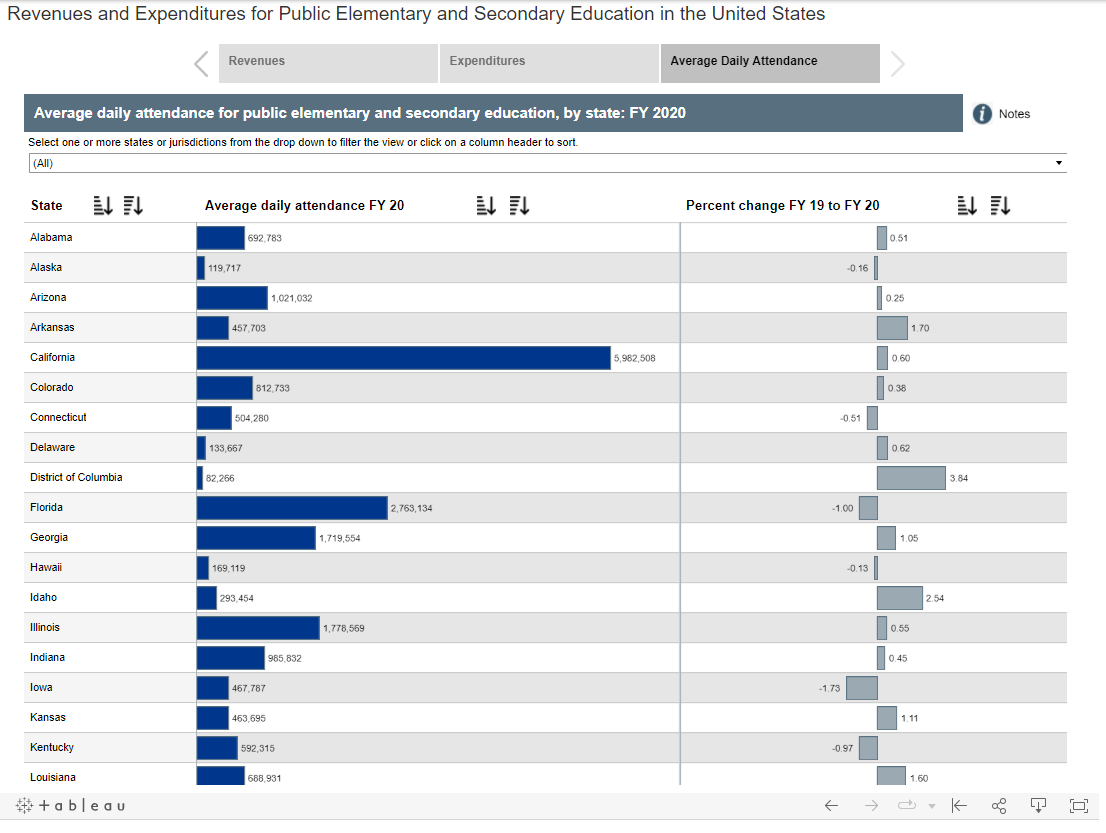

The tool also allows users to see the ADA for each state. It is sortable by state, ADA amount, and percentage change. It may also be filtered to easily compare selected states. Hovering over the ADA of a state will display another bar graph with the last 3 years of ADA data.

Revenues and Expenditures

Between FY 2019 and FY 2020, inflation-adjusted total revenues per pupil increased by 1.8 percent (to $15,711). Of these total revenues for education in FY 2020, the majority were provided by state and local governments ($7,461 and $7,056, respectively).

The percentage change in revenues per pupil from FY 2019 to FY 2020 ranged from +15.4 percent in New Mexico to -2.4 percent in Kentucky. Total revenues per pupil increased in 38 states and the District of Columbia and decreased in 12 states between FY 2019 and FY 2020.

[click to enlarge image]

In FY 2020, current expenditures per pupil for the United States were $13,489, up 0.5 percent from FY 2019, after adjusting for inflation. Current expenditures per pupil ranged from $8,287 in Utah to $25,273 in New York. After New York, current expenditures per pupil were highest in the District of Columbia ($23,754), Vermont ($22,124), New Jersey ($21,385), and Connecticut ($20,889). After Utah, current expenditures per pupil were lowest in Idaho ($8,337), Arizona ($8,694), Oklahoma ($9,395), and Nevada ($9,548).

The states with the largest increases in current expenditures per pupil from FY 2019 to FY 2020, after adjusting for inflation, were New Mexico (+9.3 percent), Illinois (+5.7 percent), Kansas (+4.0 percent), Texas (+3.7 percent), and Indiana (+3.7 percent). The states with the largest decreases were Delaware1 (-12.8 percent), Connecticut (-2.7 percent), Arizona (-2.4 percent), Alaska (-2.0 percent), and Arkansas (-1.9 percent).

Average Daily Attendance (ADA)

During FY 2020, many school districts across the country closed their school buildings for in-person learning and began providing virtual instruction in an effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In order to collect the most consistent and measurable data possible, the U.S. Department of Education provided flexibility for states to report average daily attendance data for the 2019–20 school year.

Between FY 2019 and FY 2020, ADA decreased in 14 states, with the largest decrease at 2.4 percent in New Mexico. ADA increased in the remaining 36 states and the District of Columbia, with the largest increase at 4.1 percent in South Dakota. In 43 states, the ADA in FY 2020 was within 2 percent of the previous year’s ADA.

[click to enlarge image]

To explore these and other data on public elementary and secondary revenues, expenditures, and ADA, check out our new data visualization tool.

Be sure to follow NCES on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube and subscribe to the NCES News Flash to stay up-to-date on the latest from the National Public Education Financial Survey.

By Stephen Q. Cornman, NCES, and Malia Howell and Jeremy Phillips, U.S. Census Bureau

[1] In Delaware, the decline in current expenditures per pupil is due primarily to a decrease in the amount reported for employee benefits paid by the state on behalf of local education agencies (LEAs). The state reviewed this decline and provided corrected data that will be published in the final file.