Research shows that absenteeism is related to a number of negative outcomes for students, such as lower test scores and higher dropout rates, and often occurs when students feel unsafe, especially for those who experience hate-related harassment. Victims of prejudice or discrimination, including those who are called hate-related words, also experience poorer mental health and higher substance use compared with students who experience other types of harassment (Baams, Talamage, and Russell 2017).

The School Crime Supplement (SCS) defines hate-related words as insulting or bad names having to do with the victim’s race, religion, ethnic background or national origin, disability, gender, or sexual orientation. According to the 2017 SCS, 6 percent of students overall were called a hate-related word while at school. Of students who reported being called a hate-related word, a lower percentage of White students (26 percent) reported that the hate-related word was related to their race than did students who were Black (68 percent), Hispanic (52 percent), Asian (85 percent), and of All other races (64 percent). Additionally, female students were more likely than male students to be called a hate-related word related to their gender (23 vs. 7 percent).

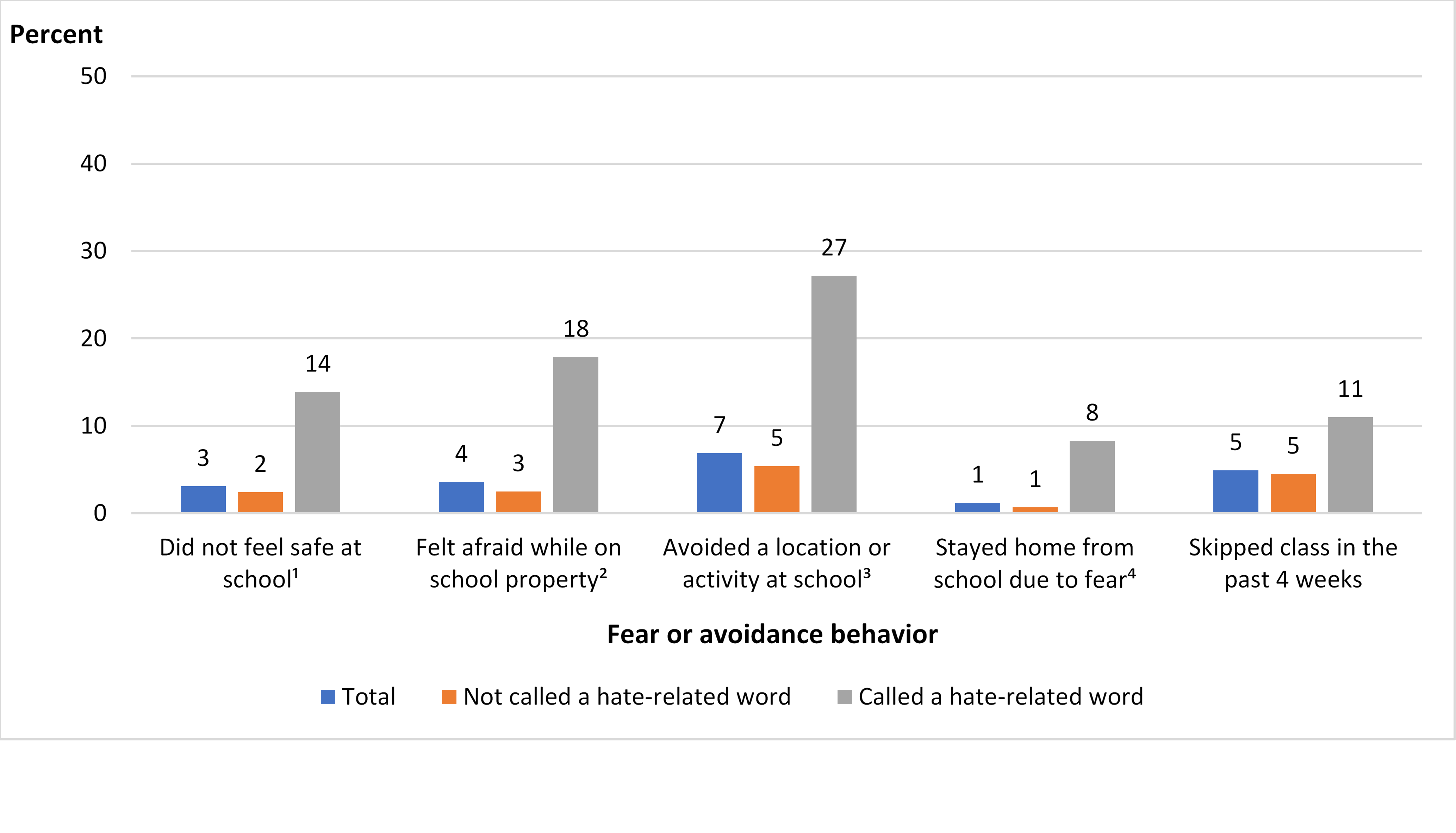

In the 2017 SCS, students who were called a hate-related word felt more fear, practiced more avoidance behaviors, stayed home more from school due to fear, and generally skipped classes more than students who were not called a hate-related word. Specifically, of those students who were called a hate-related word at school,

- 14 percent did not feel safe at school (compared with 2 percent of students who were not called a hate-related word);

- 18 percent were afraid that someone would attack or harm them on school property (compared with 3 percent of students who were not called a hate-related word);

- 27 percent avoided some location, class, or activity at school (compared with 5 percent of students who were not called a hate-related word);

- 8 percent stayed home from school due to fear that someone would attack or harm them (compared with 1 percent of students who were not called a hate-related word); and

- 11 percent had skipped class sometime in the previous 4 weeks (compared with 5 percent of students who were not called a hate-related word).

Figure 1. Percentage of students ages 12 through 18 who reported being called a hate-related word at school, by student reports of fears and avoidance behaviors: School year 2016–17

1 Those who responded “disagree” or “strongly disagree” to the following question: “Thinking about your school, would you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the following? You feel safe in your school.”

1 Those who responded “disagree” or “strongly disagree” to the following question: “Thinking about your school, would you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the following? You feel safe in your school.”

2 Those who responded “sometimes” or “most of the time” to the following question: “How often are you afraid that someone will attack or harm you in the school building or on school property?”

3 Those who responded “yes” to one of the following questions: “During this school year, did you ever stay away from any of the following places: shortest route to school; the entrance into the school; any hallways or stairs in school; parts of the school cafeteria or lunchroom; any school restrooms; other places inside the school building; school parking lot; other places on school grounds; school bus or bus stop?”; “Did you avoid any activities at your school because you thought someone might attack or harm you?”; or “Did you avoid any classes because you thought someone might attack or harm you?”

4 Those who responded “yes” to the following question: “Did you stay home from school because you thought someone might attack or harm you in the school building, on school property, on a school bus, or going to or from school?”

NOTE: Figure data include only students who reported being enrolled in grades 6 through 12 and who did not receive any of their education through homeschooling during the school year reported. Students responded to the following question: “During this school year, has anyone called you an insulting or bad name at school having to do with your race, religion, ethnic background or national origin, disability, gender, or sexual orientation? We call these hate-related words.” Population size based on the 2017 SCS for all students meeting the age, grade, and school criteria is 25,023,000.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, School Crime Supplement (SCS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017. See Table 16 in the crime table library.

You can find more information on student-reported experiences related to school crime and safety in NCES publications, including Student Reports of Bullying: Results From the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey and the 2018 Indicators of School Crime and Safety.

By Christina Yanez and Rebecca Mann, Synergy Enterprises, Inc., and Rachel Hansen, NCES

Reference

Baams, L., Talmage, C., and Russell, S. (2017). Economic Costs of Bias-Based Bullying. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(3): 422–433.