It’s important for schools to help ensure students are safe and healthy, both physically and mentally, so that learning can occur. In addition to implementing security measures on school campuses, there has been a growing focus on whether schools provide mental health services. In school year 2015–16, some 71 percent of public schools reported having diagnostic assessments for mental health disorders available to students, and 64 percent of schools reported having treatment available. [i]

These data come from the School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS). The 2015–16 SSOCS questionnaire added new questions asking principals to report whether diagnostic assessment and treatment services for mental health were available to students under the official responsibilities of a licensed mental health professional.[ii] Diagnostic assessments are used to identify whether a student has one or more medical and/or mental health diagnoses. Treatment is a clinical service, such as psychotherapy, medication, or counseling, which is intended to lessen or eliminate the symptoms of a disorder.

The prevalence of mental health services varied by school characteristics. In both middle and high schools, diagnostic assessment services were more common than treatment services: 74 percent of middle schools and 79 percent of high schools reported diagnostic assessments were available, compared with 66 percent of middle schools and 69 percent of high schools reporting treatment services were available. Compared to primary schools, a higher percentage of high schools reported that both types of mental health services were available.

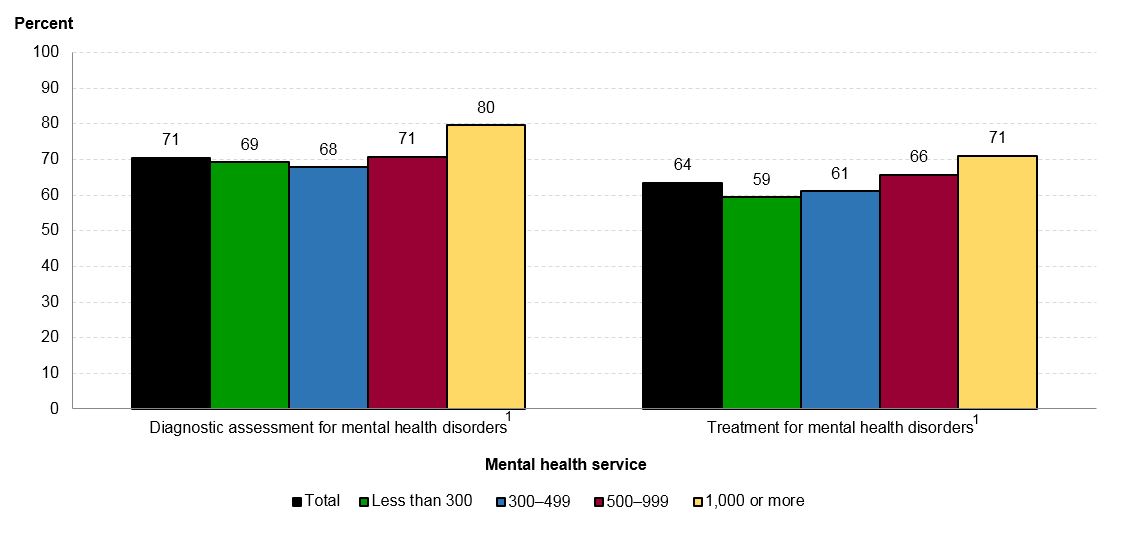

Figure 1. Percentage of public schools reporting the availability of mental health services under the official responsibilities of a licensed mental health professional, by type of mental health service and school enrollment size: School year 2015–16

1Mental health disorders were defined for respondents as, collectively, all diagnosable mental disorders or health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior (or some combination thereof) associated with distress and/or impaired functioning.

NOTE: Mental health services are provided by several different types of mental health professionals, each of which have their own training and areas of expertise. The types of professionals who may provide mental health services include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioners, psychiatric/mental health nurses, clinical social workers, and professional counselors. Responses were provided by the principal or the person most knowledgeable about school crime and policies to provide a safe environment.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015–16 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), 2016. See table 40.

The percentage of schools with 1,000 or more students that reported having diagnostic assessment services available (80 percent) was higher than the percentages of schools with fewer than 300 students (69 percent), 300–499 students (68 percent), and 500–999 students (71 percent).

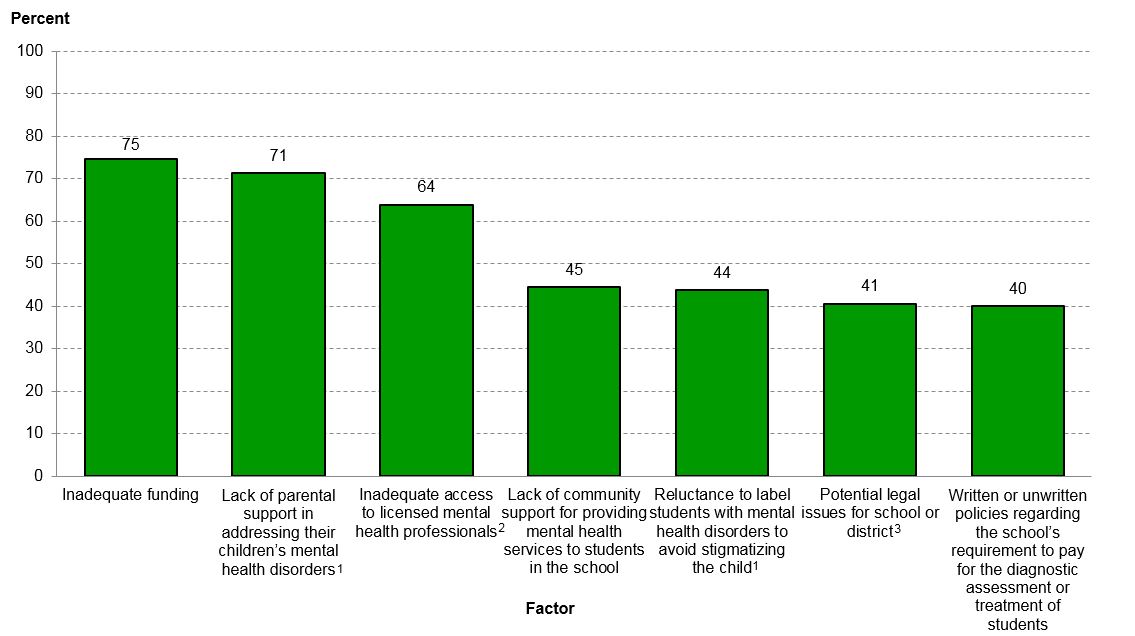

The questionnaire also asked principals to report to what extent certain factors limited the school’s efforts to provide mental health services to students. The most common limiting factors reported by schools were inadequate funding (75 percent) and lack of parental support (71 percent).

Figure 2. Percentage of public schools reporting that their efforts to provide mental health services to students were limited in a major or minor way due to specified non-school-level factors: School year 2015–16

1Mental health disorders were defined for respondents as, collectively, all diagnosable mental disorders or health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior (or some combination thereof) associated with distress and/or impaired functioning.

2Mental health services are provided by several different types of mental health professionals, each of which have their own training and areas of expertise. The types of professionals who may provide mental health services include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioners, psychiatric/mental health nurses, clinical social workers, and professional counselors.

3Examples of legal issues provided to respondents were malpractice and insufficient supervision.

NOTE: Respondents were asked to rate the level of limitation in their school’s efforts to provide mental health services to students for each factor. Survey response options included “limits in major way,” “limits in minor way,” or “does not limit." Responses were provided by the principal or the person most knowledgeable about school crime and policies to provide a safe environment.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2015–16 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS), 2016. See table 39.

You can find more information on school crime and safety in NCES publications, including Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public Schools: Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2015–16 and the 2017 Indicators of School Crime and Safety.

By Rachel Hansen, NCES and Melissa Diliberti, AIR

[i] Includes services available at school by a mental health professional employed by the school or district; services available at school by a mental health professional other than a school or district employee, funded by the school or district; and services available outside of school by a mental health professional other than a school or district employee, funded by the school or district.

[ii] The 2015–16 questionnaire provided formal definitions for many terms, including at school, diagnostic assessment, mental health disorders, mental health professionals, and treatment.